In 15 violent seconds, the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake rendered Lupin Lodge a wreck of toppled cabins and cracked foundations that took years to rebuild. Four years prior, a rare summer rain and mercurial wind-shift spared the nudist resort from a 15,000-acre arson-sparked blaze that destroyed the community water system.

But neither seismic spasms nor wildfire prepared Lupin proprietor Glyn Stout for the devastating force of Ed Dennis.

Ed moved into the clothing-optional Los Gatos enclave in 2002, a year after Glyn and his new wife, Lori Kay, had given birth to twin girls. First-time fatherhood and a second-time marriage got Glyn thinking about how to secure his family’s future by investing in the 110-acre property—California’s oldest nudist colony.

Glyn confided these hopes to Ed, a retired entrepreneur with a purported $17 million net worth and a passion for naturism. Ed—corpulent, blustery and later tabbed Terrible Ed—“portrayed himself as an unselfish paladin,” the Stouts told a judge some years later.

Somehow, the Stouts recounted in a lawsuit they filed against him in 2007, Ed persuaded them of his accolades as: “an intellectual genius, a think tank consultant on retainer with multiple Fortune 500 companies, an entrepreneur with a natural talent for creating wealth, as well as an expert in … publishing, printing, engraving, photography, computers, web design, marketing, accounting, information systems, French cuisine and fine wine, management communications, preschool education, luxury apartment development, renaissance fairs, business law, mortgage finance, mental health, psychology, team building and organizational behavior.”

This ostensibly charitable newcomer promised to help Glyn and his wife achieve financial stability, double the club’s membership and spark a naturist revival. To Glyn, saddled with debt and litigation, the man sounded like a godsend. He signed over the company—but not the property—to Ed and his wife Kassandra. On a handshake, they agreed to a 99-year lease. Trusting Ed, Glyn said, became the worst mistake of his life.

Lupin proprietors Glyn Stout (pictured) and his wife, Lori Kay, have been locked in a battle over water rights with the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District. (Photo via Facebook)

Under Ed’s brief reign, membership fell to a 25-year low. Staffers also left in droves. The already-foundering club nearly collapsed under the weight of lawsuits, liens, collections cases, sexual harassment claims and overdue taxes. The Lupin Loop newsletter, once a bulletin for community announcements, became a platform to berate members who voiced their concern.

After learning that Ed was nothing more than “a well-experienced con-man, sociopath and misanthropist,” as the Stouts characterized him in the inevitable breach-of-contract lawsuit, it took three more years of bitter court fights before the final showdown. Ed and Kassandra would hole themselves up in their cabin or the main office for days at a time. Finally, after months of sabotage, sieges and physical bouts, sheriff’s deputies enforced the eviction and ended a bitter saga that pushed Lupin to the brink of insolvency.

Glyn seemed to never quite recover from the episode. A spinal fusion to relieve a pinched nerve, compounded by cancer and other ailments, left the longtime owner frail and spent. His wife Lori Kay, an acclaimed sculptor, assumed control in 2006. Almost a decade later, as Lupin approaches its 80th anniversary in August, the resort remains shrouded in allegations of wage theft, substandard living conditions, questionable hiring practices and retaliatory evictions.

Last month, the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s Office accused Lori Kay, 53, Glyn, 77, and two resident-staffers of surreptitiously sucking water from a nearby creek. Now with a felony case on the books, longtime members wonder whether Lupin can weather its latest legal storm.

Lupin Lodge has an impressive 80-year history, but things haven't been stress free the last couple decades. (Photo by Robert Bergman, via Naked Club)

Jean Farmer, a Louisiana transplant dogged by a federal fraud charge, followed her husband Robert Cowan on a job lead to Lupin in late 2008. For the equivalent of $8 an hour, Cowan would take care of landscaping in exchange for a place to park his RV.

The couple fell in love with Lupin, named for the California flower that blossoms into a spear of purple petals. Founded as Elysium by Euro-phile naturist George Marcellus Spray in 1935, the resort offers a panoramic view of mountains and redwoods. It feels remote—with wandering deer and the occasional mountain lion. Still, it’s a quick drive from both Silicon Valley and the coast, suspended in what Glyn calls “a creative vortex” between valley industry and Santa Cruz earthiness. Some 60 or so people live on the grounds in an assortment of cabins, yurts, tents and trailers.

But there’s a saying among Lupinites: “You fall in love with Lupin, but Lupin does not fall in love with you.”

Cowan stopped working after months without payment of any kind, he said. His wife picked up a job at the clubhouse restaurant, a three-month trial starting with the holiday rush in return for rent and a membership. Farmer said she never got paid either, despite long days running the kitchen. She complained, got laid off and then sued Lupin for $70,000 in back pay and overtime.

While the lawsuit played out in Santa Clara County Superior Court and a parallel claim through the Labor Commissioner’s Office, Farmer said, her trailer’s electricity and water were shut off as retribution for alerting the authorities. The Stouts settled out of court, avoiding trial. But the case pointed to trouble in Lupin’s hallowed naturist paradise.

Records show that the Stouts have increasingly relied on tenants who barter work for rent and food, only to fire and evict many of them on short notice. “You start to feel like it’s more of a transient place,” said a former member who lived for decades on the grounds and asked to withhold his name. “People have to wonder whether they can sustain a way of life there.”

Musician Little John Chrisley says he moved into the Sleepy Hollow cabin in 2006, though his eviction papers filed by Lori Kay say he arrived in November 2010. Per his contract, he would work for $8 an hour in Lupin credit, good for meals with room and board. Chrisley, a South Bay-raised blues prodigy who played in his early days with Huey Lewis, Bo Diddley and John Lee Hooker, agreed to also host occasional concerts. Over time, his responsibilities shifted to tending the property and helping Glyn.

But a year later, in 2011, Chrisley quit and hid away in his cabin. He said that Lori Kay instructed kitchen staff to withhold meals, forcing him to salvage rice and boiled eggs from Glyn’s fridge after a full day working in the hills. Broke and paranoid, he said he felt imprisoned in a moldering cabin with a rotting-out sink and no toilet.

“Lupin traps you up on that hill,” Chrisley said. In May of last year, he was evicted for not paying rent.

“What they did to Little John was reprehensible,” said Russ Klein, a 30-year real estate broker who’s rented a cabin at Lupin for six years and said he acted as mediator between Chrisley and the Stouts. “They picked on somebody who couldn’t fight back.”

Lori Kay countered that the only time people are denied food is if they don’t have enough credit because they either stopped working or stopped paying. “No one is starving up here,” she said.

Twenty former live-ins allege similar treatment in a dozen eviction cases filed since 2009. Coraleen “Corky” and Steve “Butch” Fontanetti said they couldn’t apply for unemployment benefits after they left because work hours weren’t properly accounted for. Military veteran Adam “Army of One” Sanders and girlfriend Danielle Perkins said Lupin demanded an increasing number of work hours without overtime or holiday pay. Mildred Baker and her family said they were kicked out after alleging sexual harassment. Many of these people had no recourse due to verbal lease and work contracts. Another ex-tenant asked not to be named because he said the one thing he did sign was a nondisclosure agreement.

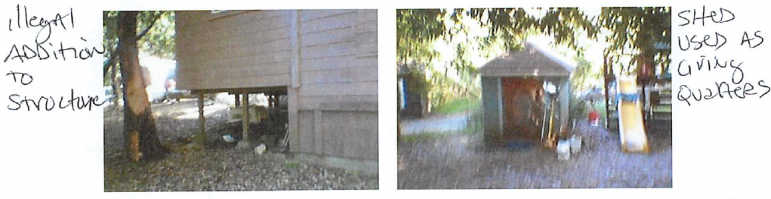

Maura Byrne moved into the Baytree cabin in 2010 and got kicked out three years later. Like many of Lupin’s jilted tenants, she claimed in court that the Stouts retaliated against her for summoning the county Department of Planning and Development after repeated requests to eradicate rats and replace a wall heater. Joe Hughes, the housing inspector who responded to her complaint, found a host of violations: inadequate foundations, a rat nest in her daughter's bed, lack of sewage disposal and a nearby tool shed illegally converted into living space.

Source: Santa Clara County Department of Planning and Development

Adding insult to Byrne’s legal injury: her car got towed at Lori Kay’s behest and she was too broke to pay the $800 to get it back. In an email dated April 18, 2013, Lori Kay told Byrne to move her car to the “Back 40,” a former storage area and now a plot of derelict trailers hidden from view to most visitors. “[W]hat you did was illegal and immoral,” Byrne wrote back. “It surprises me, given my knowledge of all your shady business practices, that you would go the route of retaliation.”

Over the years, Lupin shunted more and more staffers to the Back 40, recently renamed The Terraces, which lies off the margins of a map given to visitors and beyond a sign marked “Maintenance Area.” Rows of dilapidated trailers abandoned over the decades sit next to plastic chairs and propane tanks, tilted awnings and leak-shielding tarps. There is no plumbing or septic, only makeshift electrical wiring.

“It’s shocking to think that a place that looks like the Back 40 is so close to Los Gatos,” a Lupin tenant said. “Most people there are recovering from some setback in life. They don’t know any better.”

Many of Lupin's resident workers live in an off-grid part of the property called the Back 40.

Largely through word of mouth or “help wanted” Craigslist ads beckoning people to “come live in paradise,” residents claim, Lupin has hired people “in transition”—transitions from prison, probation, broken relationships or drug and alcohol addictions. According to both court records and internal company documents supplied by former employees, many worked for the equivalent of minimum wage in “Lupin Bucks,” basically a credit on their account to pay for lodging, meal tickets and membership fees.

“Many times we work more on a barter system rather than traditional models,” Lori Kay explained. “Over the last 80 years this has served Lupin and many of its members very well. Unfortunately it does not work for everyone.”

The property subsequently fell into disrepair and ran into trouble with regulators over labor and safety violations, as well as illegal grading and construction. One such violation, in 2010, involved a propane tank explosion that sent a burn-blistered tenant to the hospital for five days. The U.S. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration fined the management company, Lupin Heights Inc., $12,000. “If it ain’t broke, wait a week,” Lupin dwellers often quip.

Though not certified as a sober-living environment, Lupin has also presented itself as a place to get back on one’s feet. “They deliberately look for people who are in a desperate situation,” said Klein, who almost moved out several times because of what he calls rampant and passively accepted methamphetamine use on the grounds. “They have a twisted notion that they’re some kind of a rehab.”

Lupin’s membership materials appear to support that claim. “Over the years, Lupin has been a haven of sobriety for many who have learned that their lives depend upon avoiding alcoholic consumption,” a handout states. Felony drug use, it continues, results in automatic dismissal. In practice, however, that wasn’t the case.

A couple years ago, the county’s Department of Family and Children Services took custody of newborn twins from their meth-addicted mom, a chef at Lupin’s restaurant. The mother, identified in court papers only as J.A., told the judge that she lived in a “zero-tolerance” community at Lupin. In its response, the county discredited that notion, pointing out that Lupin holds a liquor license and only bans alcohol from the pool and spa.

Still, many former and current residents said that they came to Lupin looking for some measure of healing, only to get swept up in a cycle of codependency by relying on the Stouts for housing, food and work. One couple said they had to sign up for public welfare because the Lupin credits they earned didn’t cover for enough meal vouchers. Former Cabrillo College instructor Robert Eckert, who moved into the Tiger Lily yurt in 2009 as a paying tenant before getting evicted a year later, said he would sometimes give staffers rides to the food bank so they could eat.

In a phone conversation with San Jose Inside, David Benfell, a graduate student who lived at Lupin from 2002 until he moved out on his own accord in 2008, said he became disheartened by the stark socioeconomic divide between paying members and the live-in workers.

"I saw people 'down on their luck' brought into a place where, yes, they were surrounded by incredible natural beauty, but where they were still 'down on their luck,' and hopelessly trapped in an abusive condition," he wrote on his blog in 2013.

There’s another adage in the camp that Lupin employees are more likely to have an outstanding warrant than a valid driver’s license. The Stouts dispute the assertion, saying the club performs background checks and sometimes drug tests to screen employees, though a criminal conviction won’t necessarily disqualify a person from moving in. In fact, a considerable number of resident-workers came to Lupin with checkered pasts—commonly with domestic violence, drug and theft convictions—and often brought their troubles with them. Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office spokesman Sgt. James Jensen said that in the past two years deputies were called out to Lupin once every eight days on average.

Thirty-eight-year-old Mike Buckland, one of the two resident workers caught up with the Stouts on water theft charges last month, came to Lupin with a mile-long rap sheet and nowhere else to go. The Stouts gave him work, a trailer to live in and food from the kitchen—which got temporarily shut down for vermin by county health inspectors last month.

Eviction records state that Lori Kay’s half-brother, Ricky Mendoza, began working at Lupin in 2008. Court records indicate he was an ex-con battling addictions to meth and heroin. Already a wiry 5-foot-5, Mendoza began wasting away from drugs—in virtually every arrest report, police said he was coming down from some kind of high. During his stay at Lupin, police say they caught him with drugs, blank checks and stolen cars.

The week between Christmas 2008 and the New Year, Mendoza, high on meth and heroin, stole a 2002 Mitsubishi Gallant and high-tailed it past the Great Mall in Milpitas, according to court records. Police described him as thin and rank, with a shaved head and a goatee. Panting and drooling, he curled up on the ground in a fetal position and said he felt like his heart would explode.

“My stomach’s hurting,” he told the officer, admitting he’d been using drugs all day and, in a panic, had just swallowed a gram of meth. “I’m going to die.”

Mendoza’s sister, Lupin owner Lori Kay, formally evicted him from his trailer in 2014. By then an exodus was occurring for many longtime members. Some defected to other clubs, fed up not just with the drugs but also the all-night raves and fetish parties that they felt flouted the wholesome ideals of naturism.

Born to a strict religious Filipino father and blue-eyed, blonde Virginia-bred mother, Lori Kay shed the surname Mendoza in her mid-20s after establishing a new life in the Bay Area. While attending UC Santa Cruz as a art history major, she spent time studying abroad in Switzerland, where her host family introduced her to naturism and the body acceptance movement. Upon her return, she discovered Lupin, where she would meet Glyn and raise their two daughters.

One of Lori Kay's sculptures, titled Flight IV, installed at a Fremont fire station. (Photo via City of Fremont)

“It’s an incredibly beautiful place,” she said proudly, gesturing to a sweeping view of redwood forest beyond the floor-to-ceiling windows of the Lupin restaurant.

A celebrated mixed media artist and metal sculptor, Lori Kay has exhibited and lectured both locally and abroad. Her work has been commissioned for public art projects in nearly a dozen cities. Through her art, she has explored themes of identity and a childhood marked by prejudice against her interracial parents and their mixed-race offspring.

“I needed to stop and do this,” she says in a 1995 Mercury News article about an exhibit inspired by her biracial heritage. “I couldn’t just keep going casting bronzes and doing public sculptures without questioning … who am I, and how do I bring both my backgrounds to who I am and what I create.”

There’s a stark contrast between Lori Kay’s ruminative artistic self depicted in old news clippings and the portrait painted by court records and accounts from dozens of embittered Lupinites. Tenants and members describe Glyn and Lori Kay, who live apart on the grounds, as a “good cop, bad cop” duo. Glyn is quick to commend his semi-estranged wife—the pair filed for divorce but never finalized papers—for her ability to take charge.

“I’m basically a Los Gatos soccer mom,” she said, “except there are three very unusual things about me.”

For one, she’s mother to a fifth generation of mirror-image twins. High school-aged Simone and Samara are identical but with opposite asymmetric features—one is right handed and the other left, one’s hair whorls clockwise and the other counter. Secondly, Lori Kay said, she’s a female sculptor. And, of course, she manages the longest-running naturist club west of the Mississippi.

“The oldest business in the Los Gatos chamber of commerce,” she said, adding that she intends to keep it that way.

Lori Kay dismisses allegations from former tenants as sour grapes from people who dropped their end of the contract. Lupin won those cases, she pointed out, and the people evicted have questionable reputations and legal troubles in their own right.

“We evicted them as any landlord would,” she said. “We are much more careful in the way we investigate potential tenants in an attempt to minimize the number of evictions.”

Most of Lupin’s visitors have been loyal members for more than 10 years, she said. “Our membership has supported Lupin through some tough times,” she added. “They love Lupin. Many comment that Lupin and the environment that it provides has helped them with negative body issues. The peace and tranquility of Lupin has helped people through tough times in their lives.”

Robert Bergman, a photographer who flies in from Canada every year to organize a body acceptance festival at Lupin said any facility that size will have issues, but that his experience has been positive on the whole. Delman Smith, a Los Gatos-based attorney and Lupin member for decades, agreed, calling the place “Eden-like.”

Citations from various regulatory agencies, Lori Kay said, are simply one of the challenges of running an unconventional business—one that’s part water district, wildlife refuge, mobile home park, tourist attraction and bastion of a widely misunderstood subculture.

“We try our hardest to continue in our 80-year tradition in having a safe, family friendly and mutually respectful place,” she said. “We’re a community.

But even within the tight-knit naturist community, Lupin has alienated some members by blurring the line between sex and social nudity.

“Being a nudist is supposed to be a non-sexual, family friendly environment,” explains Ken Hooper, who canceled his membership in the mid-aughts over what he saw as the club’s decline. “That’s so important. Social nudity is about trust.”

After a breathless chase through the steep, forested hillsides, a shiny fox with a bouncy inflatable tail succumbed to his captor. Smash—a 39-year-old man in a latex fox suit with zippered crotch—gleefully whimpered and caressed his potbelly as the hunter rubbed his nipples. “He’s in fox heaven,” an onlooker said with a laugh.

Smash, star of the human fox hunt. (Photo via Flickr)

Journalist Tracy Clark-Fory documented the bizarre ritual of the “Human Fox Hunt” at Lupin for Salon in 2011. She described men and women dressed up in leather and harnesses and erotic, anthropomorphic animal costumes stalking each other in the woods.

“There is a jarring dissonance between the back-to-basics naturist routine and the sinister ornamentation inside the hut,” Clark-Fory observed.

Punishment for the foxes apparently involved some sort of agreed-upon BDSM play in the privacy of a rented yurt. Even if the sex happened out of public view, the sexualized role-play at a resort marketing itself as family-friendly sent shockwaves in naturist circles.

Not long after the hunt, the American Association of Nude Recreation (AANR) withdrew its accreditation from Lupin Lodge.

Cindy Gregory, a resident member and Lupin’s special events coordinator, wrote an open letter to AANR defending the decision to rent space to the fetish party. After all, she said, at least some of the kinky cosplayers shed their “furversions” to a polite nakedness after the hunt. Being outnumbered by “textiles,” as nudists call the clothed, can stir up insecurities for naturists.

“After the hunts, many of the participants took off their costumes and enjoyed the hot tub and pool in the nude,” she assured AANR leaders, adding that there was no public sex on the grounds. “I am gratified that they feel accepted here and comfortable enough to express themselves.”

Other non-naturist groups would rent out spaces for parties, all-night raves that drew the ire of neighbors and the attention of sheriff’s deputies. Months before the human fox hunt, a 21-year-old raver rolling on molly and four tabs of acid collapsed in the main bathroom—called the Taj Mahal by Lupin residents. Another partygoer found him around 6am, slumped over and vacant, and called 9-1-1. Paramedics recounted in incident reports that his blood pressure shot up and his brain swelled before he died.

“That should have woke us up,” a resident lamented. “By the time the next guy died, a lot of us had enough morally, ethically. We had to say something.”

Michael Schaupp left Santa Cruz around midday Dec. 10, 2013, for a 2pm class at Ex’pression College in Emeryville. The 36-year-old father and design student had driven the same northward Highway 17 route countless times on his 1996 Honda VLX motorcycle. Drivers who shared the winding mountain road with him that day said he looked at ease, like an experienced rider. And he was.

But about a half-hour into his commute, a 1994 Ford Explorer shot out onto Highway 17 from Idylwild Drive in a southbound arc that cut off Schaupp and sent him hurtling to the shoulder, according to detailed reports by California Highway Patrol officers. A trail of blood plotted his trajectory. The Explorer’s 47-year-old driver, Joline Faye Cohen, scrambled out of the SUV just as another car pulled up to the scene.

Michael Schaupp. (Photo via www.themikeschaupp.com)

“Oh my God, I just killed that guy,” she told the witness, per the CHP. “Did you see him hit my car? What should I do?” Without waiting for an answer, she hopped back in the driver’s seat and drove away. A second witness pulled onto the shoulder and put a blanket on Schaupp, protecting him from the winter chill until help arrived.

A short distance north, Cohen, in a long black coat and dry dirty-blonde hair, left her car at Bear Creek Road and began walking along the shoulder, the collision report continues. Campbell resident Brandon Rohzen told police that he picked her up in his minivan, thinking she’d just got into a fender-bender and could use a lift. From the passenger seat, he said he remembers her calling Lupin’s office landline. “I hit somebody,” she shouted hysterically. “I think they might be dead.” Horrified, Rohzen slammed on the brakes and told her to get out of his car.

Schaupp died two days later at Stanford Hospital. Yet three full months passed before Cohen surrendered herself to authorities on hit-and-run charges that landed her in a Central Valley women’s prison.

Lupin residents claim Lori Kay harbored a fugitive during that time, leaving them no choice, they said, but to tip off CHP investigators to Cohen’s whereabouts. As a live-in assistant for several years to Lori Kay, Cohen ran errands, oversaw the main office and, according to CHP tipsters, had a reputation for smoking meth and driving erratically. Lupin management tried to distance itself from the damage, announcing online that the club had fired her as office employee before the crash. “She was allowed to stay because there are such things as tenancy laws,” Lori Kay explained.

But the tragedy raised more questions about Lupin’s hiring practices. In an ongoing wrongful death lawsuit against Cohen, Schaupp’s mother, Denise, and 19-year-old son, Caleb, also name Lupin as a defendant. The Schaupp family attorneys claim that Cohen was acting “within the scope of her employment” while driving the SUV and that Lupin is vicariously liable because it employed her “with knowledge of her history of reckless driving, erratic behavior and substance use.”

“That was the beginning of the end for me,” says a member who has called several government agencies to investigate Lupin. “You can’t run from one crisis to another and blame the rest of the world.”

Because it’s a pending case, the Stouts declined to talk about the wrongful death lawsuit, except to insist that they fired Cohen before the fatal accident. Attorneys also advised them against talking about the alleged charges of stealing water from a creek managed by their neighbor, the Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District.

Prosecutors say the Stouts and two resident employees siphoned thousands of gallons from Hendry’s Creek last year without permission to offset a drought-induced water shortage. Wildlife cameras allegedly caught the foursome in the act, trespassing to route a plastic pipe from Hendry’s waterfall. The Stouts claim their rights to the water were grandfathered in—the former landowner allowed them to tap the stream before selling the property to the open space district in 2012.

“This is the latest setback,” Lori Kay acknowledged last week. She added that Lupin has survived worse—the Great Depression, World War II rationing, fires, droughts and earthquakes—and the legacy of the lodge is bigger than any one person.

Yet many members, some of whom spent the better part of their lives at Lupin, fear that the eight-decade legacy has been corrupted by deep-seated dysfunction, and the water has run dry in more ways than one.

Very informative story using just the “bare facts.”

Good Reporting Jenn W.

David S. Wall

Lupin Lodge is a nice resort for nudist! once been there and enjoy it!

I would suggest that you either get a base tan, or apply sunscreen liberally. Nobody will care what you look like, and you might find there are others that are a bit more out-of-shape than you! Check LocalNudistSingle com to give yourself a better chance by meeting nudist singles who enjoys the same nudist lifestyle that you do!

ya,maybe they should give you free tanning lotion on the days there are police raids..

Police raids? What century are you living in? Lupin has been there for 80 years or so….the police don’t care…in fact, more than likely, there are, or have been, a few law enforcement personnel who were members or casual visitors over the years.

yes warren..police raids..one every 8 days for the last 2 years on average…you can find the century im living in elsewhere.

John, you’ve misquoted Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Office spokesman Sgt. James Jensen:

“…in the past two years deputies WERE CALLED OUT TO Lupin once every eight days on average.”

These were not raids by police, these were responses to calls for assistance from members, residents & employees of Lupin.

“Lupin traps you up on that hill,” Chrisley said. In May of last year, he was evicted for not paying rent.

I lived a few years one road up from you on Laurel when I was in High School. As a teen without a car, ya I felt pretty trapped up there (only laurel is one helluva last push compared to just going to Lupin)

I also visited Lupin.. Alot. Between 1989 and 1991. Summer would come, and I’d sneak a dip in the pool. Never got caught going by myself, but one time I brought some friends there and… Sheriff. Ah well, lesson learned.

Finally someone tells the truth about Lupin. Good job Jenn.

why not enjoy nudist lifestyle

yes the nudist/naturist lifestyle can be truly enjoyed at aanr endorsed clubs..lupin is not one of them..

An interesting case study in “tribalism”.

Probably mirrors the way humanity lived 10,000 years ago before the invention of herding, agriculture, private property, and individual “rights”.

The “shaman” ran the show: leader, warlord. medicine man, pope, judge, and jury all in one.

My way or the highway.

Here’s a prayer that the besieged couple who own he park get their problems worked out, get more membership and visitors, and restore the park, one part at a time to its original glory. Unfortunate things happen, but with a positive attitude things can be worked out. This article seemed to be a bit of an overkill to me. Bad health, and an earthquake was certainly not their fault. The barter system is a good workable idea as long as the barterer continues to keep his part of the bargain. When he does not, of course bad feelings result when that person is kicked out. Let’s all wish them well as they go forward to the future.

pathetic and insensitive of you to offer up a prayer to the stouts and bypass michael schaupp and his family.

You all will enjoy the article my photojournalist father, Sam Vestal, wrote about Lupin for the Watsonville Register Pajaronian SIXTY years ago: https://www.facebook.com/samvestalphotography/photos/pcb.473944266101957/473944069435310/?type=1&theater

Why is it being characterized as a problem, that some people at the Lupin community, apparently like to do meth? I have it on good authority that some people in the city of San Jose, like to do meth too, LOL. Meth’s actually everywhere, Aunt Martha.

MAYBE @scvwd @valleywater.org should invest, they are crooks at everything else, maybe buy stock?

http://kron4.com/2015/07/13/owners-of-los-gatos-nudist-lodge-arraigned-for-allegedly-diverting-water-from-creek/

I was a frequent visitor to Lupin when I lived and worked in the San Jose/Santa Cruz area. I am acquainted with Lori Kay and Glyn and briefly considered taking a position of general manager when their then manager was retiring. Although it was a very fluid discussion about what the position, pay, responsibilities etc were in actuality. I found them difficult to nail down on almost anything. I’ve found it’s best to make sure that everyone understand the terms of any deal before entering into it, otherwise there will undoubtedly be unmet expectations on somebody’s part. Many of the the claims reported above became clear to me during this time. The drug abuse while somewhat hidden from visitors and while officially not tolerated by the management was definitely part of the subculture enjoyed by what seemed to be an indentured staff. There was a palpable sense of desperation among the staff. The barter system works great if the credit one is given in return for the labor is enough to cover their needs and if everything you need is available for purchase with your credit. People have needs beyond room and board and food. I gave numerous staffers rides into Los Gatos to the CVS there. I got to know a few and it was apparent that they were at Lupin’s mercy. They had no where else to go, and no way to get there even if they did. To be fair Glyn and Lori Kay were working with an aging membership that was declining in numbers. Ed had run large numbers off and in his absence they weren’t returning. Gentrification was taking it’s toll on membership. To Glyn and Lori Kay’s credit they understood that they had to change the status quo at the lodge to attract new younger visitors and members. The raves and the fetish parties are attempts at doing just that but more so at bringing in much needed funds for the ongoing operational costs of the lodge. I sat one morning watching a crew of Lupin’s finest work (I use the term loosely) on several small projects. One guy was working on a remodel of a small cabin. This project had been going on for weeks and it was nearing completion. Now in all honesty this cabin should have been torn down and replaced from the ground up. It was small enough that with a coordinated effort and proper scheduling of the trades involved that the thing could have easily been replaced in a couple weeks. So this fellow gets dropped off by the foreman of their construction crew and he sets up his work area tools, saw horses etc. He goes inside to measure something and comes back out. Now all this going on with a liberal amount of swearing, and kicking things around. He finally gets his saw set up and looks around for the board he wants to cut. He finally finds it and goes back in to measure again. He comes out puts a mark on the board and cuts it. Hooray. He goes into the cabin and you start hearing all the swearing and he comes out looking around the ground, kicking a few things and stomps off towards the back 40. 20 or 30 minutes later he comes stomping back with another board in his hand. he goes in to measure again, comes out and cuts the board. He takes it inside and soon you hear the swearing again, but this time you also hear the hammering. He comes out looks around on the ground for something for a little while until he again stomps off to the back 40. Another thirty minutes and he returns with another guy. They go into the cabin talking back and forth and they both come out and stomp off toward the back 40. This went on all day. He installed almost nothing all day. I was curious so I went into the cabin which was a one room approximately 12’x8′ area. It was made up by a small living sleeping area and a smaller still breakfast nook area. There were no appliances (it looked like an under counter refrigerator may have gone in later) and a sink. No restroom. It looked new inside, with fresh paint and newly repaired countertop. The flooring was new but the floor sloped easily 2″ from one corner to the other. The outside was dilapidated with pieces of siding replaced here and there and none of it matched. Plain flat plywood, plywood with vertical grooves (T1-11) and ship lapped pressboard siding. It was obvious that they used whatever was available. If it was any better off than when the work started it must have been in horrible condition. I spoke to Lori Kay who seemed pleased with how it was coming along. I explained that the crew was basically incompetent, lacked any sense of direction, there was no planning involved, materials weren’t readily available, inefficiency was the rule rather than the exception, and that although she was paying very little for the work she was getting even less for it. Lori Kay didn’t appreciate my take on things. She spoke of the “Lupin Way” of doing what it takes, coming together as a community, overcoming adversity through communal…. blah, blah, blah. Okay that’s all fine if your are living on a commune, tending bees, and selling honey to get by. But Lupin is a business. It is a naturist lodge, on edge of the silicon valley, trying desperately to attract new visitors. Clearly on the edge of no longer existing. I explained in my opinion “doing what it takes” wasn’t getting it done. The Lupin way no longer supported modern expectations for the accommodations and amenities of such a business. I asked them both to take a trip to Costanoa near Ano Nuevo, Sycamore Mineral Springs in Avila Beach, and El Capitan Canyon North of Santa Barbara to see models of what could be. Sure these were not naturist resorts. They were modeled in more of an eco-tourism model but they share many similarities and if marketed correctly the naturist component would be the icing on the cake. I explained that they needed to act on what they knew needed to be done. Gain a vision for a new Lupin, and develop a master plan for shepherding it there. I understood in the wake of Ed their wariness of partners but without the influx of some serious capital they were going to find it difficult to make the change. This Lupin way is at the root of all their troubles. When you can only offer room and board in exchange for the labor of others you are not going to be able bring quality staff on board. Your going to get folks that are in a desperate situation and everything that is listed in the above article is what comes with that. You have to feel sorry for the Stouts to an extent, they are trying their best to hold on and keep it all going but its a war of attrition. Unfortunately I think they are too bogged down in the muck and the mire of it to see a way out.