It’s July of 2019, and movie-and-pot-obsessed comedian Doug Benson has just arrived in Bend, Oregon to see the last Blockbuster Video store on Planet Earth. Before entering, he walks up to the sign to snap a selfie, laughing at the absurdity of the moment. “I can’t believe I’m at the only Blockbuster in existence,” he says.

Inside, he saunters through the aisles and cracks jokes about films he passes. He proclaims that both Paul Blart movies are in stock (“Total Blart-ocity”), and that they’ve left shelf space “to finish the trilogy.” At the “Employee Picks” section, he praises Zach’s choices but lambasts Brittany and Erika’s terrible picks. He rents Super High Me—his own movie—and cracks up when he reaches into his wallet and finds an old Blockbuster card from who knows what year.

During his Blockbuster experience, Benson is so overtaken with youthful excitement that he grabs the Big Sick DVD, and sends a photo of it to its writer/star—his pal Kumail Nanjiani— making sure the Blockbuster sign is in the background. “Dude, your movie is in the last existing Blockbuster!” he texts.

This combination video-store trip/time warp is documented in the new documentary The Last Blockbuster, released this week. At the end of the scene, Benson has a serious moment, when he muses to the camera: “I didn’t miss Blockbuster until I was in this Blockbuster. I had moved on. But now, just seeing it and being here, I love it. Who doesn’t love Blockbuster?”

In fact, many, many people didn’t love Blockbuster, at least at the height of the company’s success.

The Last Blockbuster, from indie filmmaker Taylor Morden, charts the rise and fall of the company, a story that many people have misconceptions about—like the assumption that the almighty Netflix alone put them out of business. What actually happened was much more complex. But the real heart of the story is the store in Bend. It’s an unlikely, underdog story about how this final store, against all odds, fought the changing tides of culture to turn a lone Blockbuster video store into a profitable, sustainable business.

Video Empire

BLOCKBUSTER AND CHILL A couple picks out a movie at the last Blockbuster on Planet Earth in The Last Blockbuster. (Courtesy of The Last Blockbuster)

The first Blockbuster opened in Dallas, Texas in 1985. At its peak in 2004, Blockbuster had 9,000 stores globally. Blockbuster became the giant in the industry through a series of arguably unsavory tactics, including opening stores next to local, indie video stores and pricing them out of the market.

Another of those strategies was to create revenue-sharing contracts with the movie suppliers. At the time, studios charged video stores $60-plus for new releases. With Blockbuster, they’d sell them movies for less, and take a percentage of the rental revenue. This allowed Blockbuster to buy 100 or more copies of new titles and guarantee their customers that they’d be in stock. It was a promise the mom-and-pop stores paying full price could never afford to make.

Blockbuster also created a sensory experience that was family-friendly, safe, and predictable. There was absolutely no difference from one Blockbuster to the next in any conceivable way.

Joe McAbee, who worked at Blockbuster stores in Capitola, Watsonville and Santa Cruz from 1994 until 2000, recalls how important uniformity was to the company.

“They would tell us, ‘The great thing about McDonald’s or Burger King is that no matter where you go in the country, you know exactly what you’ll get. The higher ups would always preach that,” McAbee says.

While he worked at the Capitola store, they were bringing in the third-highest revenue in the country, $40,000 a week, most of which was literal cash. The Santa Cruz store he worked at was clearing only about $9,000, as many residents preferred the indies like Mission Video over the corporate giants.

Even as Blockbuster nearly had the market cornered, there was a shortsightedness—and arrogance—to their success. McAbee recalls the way those at the corporate office would brush off illegal download sites like Napster.

“The bigwigs would always tell us, ‘Blockbuster will never go out of business because they can’t replicate what we have here. People want to take their families out on Friday and Saturday night, and come in and see the massive amounts of cover boxes. They want to talk to you and get recommendations. They love this environment. It’s an experience,” McAbee says. “Once the streaming services came, the fall was pretty quick.”

The Big Netflix Mistake

Oddly enough, Blockbuster could have owned Netflix. In 2000, Netflix founders Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph offered to sell for $50 million, but Blockbuster execs laughed them out of the boardroom.

By 2008, the two companies were competing to be the leader in the DVD rental business, with rent-by-mail being the primary means of distribution for Netflix, which held its strength in capital and good ideas. Blockbuster, on the other hand, had assets and name recognition, but they had a lot of debt from poor decisions, like ending late fees, a history of terrible management and even worse investments.

When the recession hit, Blockbuster’s debt became a death sentence while Netflix had the capital to grow. While Netflix grew into the biggest streaming service in the world, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy in 2010.

“If it wasn’t for the bad business decisions and all the debt that they were saddled with, they could have come out, if not on top, they would still be one of the top ways that we get movies, and it would probably be a streaming service,” says Morden, who produced and directed The Last Blockbuster.

South Bay Stalwart

At one time, there were Blockbusters throughout the South Bay: 11 in San Jose, as well as two in Sunnyvale and one each in Santa Clara, Cupertino, Saratoga, Milpitas and Morgan Hill. As they shut down one by one, the Japantown location in San Jose became one of the last Silicon Valley holdouts. In 2011, local Nate Kavanaugh got a part-time job there, thinking it would be fun, but business was incredibly slow, nothing like the long lines he remembered as a kid in the ’90s.

One of Kavanaugh’s most distinct memories was the volume of people coming into the store not to rent a video, but to ask if they were going to close soon.

“We were always told to say, ‘Most stores are closing, but this one isn’t; this one’s here to stay,’” Kavanaugh says. “Obviously, that wasn't the case.”

He didn’t last long, finding himself fired for not pushing candy sales aggressively enough on the store’s few customers. When it closed a little while later, Kavanaugh wasn’t shocked in the slightest.

In 2013, Blockbuster closed all remaining corporate stores. Franchised locations could continue if they wanted to, but they had to pay a licensing fee to Dish Network, and they would get no support from the company. They were on their own, essentially, as small, independent businesses. There were only a few hundred left nationwide.

Be Kind, Rewind

RUN TIME Actor and writer Brian Posehn was a mainstay in film during the height of movie rental stores, known for the 2002 comedy Run Ronnie Run. (Courtesy of The Last Blockbuster)

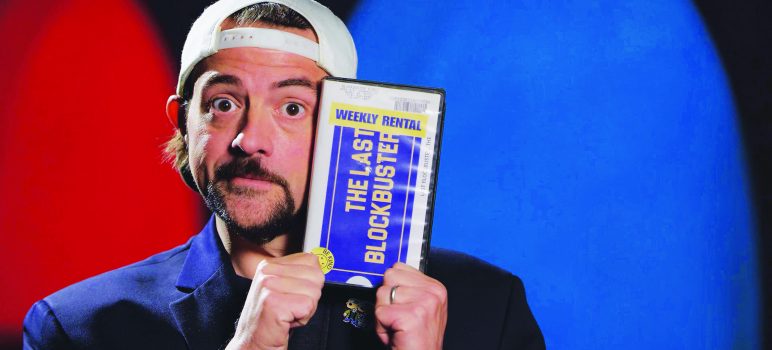

While there is plenty to criticize Blockbuster for, The Last Blockbuster stays generally positive. Of their interviewees, which include comedians and pop culture icons like Kevin Smith, Brian Posehn, Ron Funches, Ione Skye, and Paul Scheer, no one breathes a negative word about the company. That is, except for Lloyd Kaufman, head of schlock film company Troma.

Immediately following Benson’s question about who doesn’t love Blockbuster, Kaufman responds, “I can’t think of anything to say nice about Blockbuster.” Morden includes 112 seconds of the footage of Kaufman railing against company.

Kaufman’s position is understandable. Blockbuster rarely carried obscure indie films like the ones Troma made. And they were actively pushing out the indie video stores that would carry those titles.

“When we started, we thought more people would be anti-Blockbuster,” Morden says. “You remember them fondly, and you go, ‘I do miss renting videos.’ What you’re thinking of is the ma ‘n’ pa store, but Blockbuster is just a stand-in for any video store.”

The star of the documentary is Sandi Harding, general manager of the Bend store and a Blockbuster employee since 2004. The friendly and charming “Blockbuster mom” makes her staff and regular customers feel like family. She knows all their names, jokes with them and works long hours when needed to make sure everything is done at the business. Harding’s infectious and humble energy, no-nonsense attitude and her willingness to pull up her sleeves and do what needs to be done has the odd effect of making the film’s viewers cheer on Blockbuster as the scrappy long-shot in a world that’s moved past them.

But it’s not Blockbuster we’re rooting for; it’s Harding and the Bend Blockbuster owners Ken and Debbie Tisher, who opened Bend video chain Pacific Video in 1990. In 2000, Blockbuster came to town and basically gave them the option of franchising their four stores or being put out of business by a competing Blockbuster store that would be placed next to their main location. They decided to franchise, but kept a sign on the door: “This store is locally owned and operated by Pacific Video.” The sign is still there to this day.

“Meeting Sandi and being won over by her energy and enthusiasm and joy made the movie what it is,” Morden says. “It’s not just about Blockbuster, it’s about these people in this family store. … It’s like David and Goliath, but David became Goliath. But then Netflix became Goliath and they were David again.”

Reality Bends

In 2015, Morden moved from Washington, D.C.—where he shot corporate videos, commercials, music videos and weddings—to Bend, a growing, working-class Eastern Oregon town.

There wasn’t corporate video work in Bend, so he shot the feature documentary Here’s to Life: The Story of the Refreshments, about the Arizona band best known for penning King of the Hill’s theme song. It was released in 2017.

Shortly after the move, he noticed a Blockbuster near his house that was going out of business. He thought it odd that Bend was late to closing their Blockbusters, but went inside and scooped up cheap DVDs and video games, like we all did when a video store closed.

A little while later, he noticed another Blockbuster sign in an unglamorous, slow-paced strip mall in a different part of the city. He assumed it was also closed, but that no one had taken the sign down yet. By the summer of 2016, the sign was still up, so he got curious and poked his head inside, amazed to see it was open. Not only that, but it looked and felt just like a 2005 Blockbuster, but with the latest Star Wars film on the New Release shelf.

“I was blown away by the feeling,” Morden says. “It’s like when you see Doug Benson go into the store in the movie. It blew me away. It smelled the same. It looked the same. It felt the same. It was a weird trippy thing going into a Blockbuster Video.”

With a little research, Morden discovered that there were still 12 Blockbusters open all over the world, three of them in Oregon (Bend, Portland and Redmond, which was 15 minutes from Bend). In early 2017, he got the idea to shoot a web series on the final 12 Blockbusters. He asked the Tishers, who owned the Bend and Redmond stores, for an interview. They were happy to help, but said the person he needed to talk to was Harding—she was the heart of their stores.

Harding was a workhorse, but also made time to chat with anyone who walked in the door and making them feel welcome, Morden observed. But she’d never done an interview and the idea of being on camera made her nervous. More than that, she was genuinely confused why Morden wanted to interview her.

“I was taken back. I started in ’04 and got to watch the demise of Blockbuster. By the time corporate was closing, everybody thought we were a joke. The fact that somebody wanted to come interview us about being a Blockbuster store, I’m like, ‘Why?’”

Her opinion about the interest in Blockbuster would change in 2018 when comedian John Oliver aired a segment on his HBO show, Last Week Tonight, where he donated a gaudy jockstrap Russell Crowe used in Cinderella Man and other movie memorabilia to the Blockbuster in Anchorage, Alaska. Though the segment didn’t mention the store in Bend, soon it would be commonplace for Harding to stand in front of a TV camera and carry on a conversation like it was just an ordinary part of the day.

But in 2017, it was only Morden that took an interest. She agreed to interview at that time with some reluctance.

“I was scared to death that day when we did the interview. Taylor knew that and he did such a beautiful job of calming me down. And making me understand that it was going to be quick and easy,” Harding says. “We kind of chuckled. Now I do interviews all the time.”

Last Place

THE UNDERDOG Sandi Harding is the jovial and instantly likeable general manager of the Bend, Oregon Blockbuster store. (Courtesy of The Last Blockbuster)

Business was slow then, but Harding did everything she could to make it work. She stopped renting video games. She took over whatever jobs she had to do to cut costs. She even drove around to pick up and deliver supplies to save on postage.

“We had to pull up our bootstraps quite a bit during those years and make some cuts and some tough choices,” Harding says. “We did what we had to do. A lot of small businesses out there know exactly what I’m talking about.”

In March 2019, the Bend store became the last official Blockbuster on earth, after the second-to-last store in Australia closed its doors. Overnight, everything changed. Suddenly everyone wanted to visit this store. Harding, seizing the moment, upped her merch game. She changed everything to say “The Last Blockbuster” instead of just “Blockbuster.” She made a point to work exclusively with local vendors—and even with some items, like with the Blockbuster beanies, knit them herself in-between long hours of doing her actual job as store manager. The publicity brought tourism, but the locals loved it, too.

“It’s become a point of pride for the town. Whenever a friend visits a person that lives here, they’re going to say, ‘Hey, you want to go check out Blockbuster? We've got the only one in the world,’” Morden says.

Even celebrities started making the trek. In October 2019, film director Ron Howard visited the store unannounced. No one recognized him, including Harding, who overheard his conversation with a staff member, but was too busy working to look up and realize who was doing the talking. It wasn’t until Howard posted a Blockbuster selfie to his Twitter that anyone knew what happened.

“When we have celebrities come in, a lot of times, they don’t announce who they are. They just want to come and experience it like everybody else,” Harding says. “Trust me, I would have got my picture with him if I would have realized it was him.”

The last Blockbuster remains a profitable business, largely from video rental revenue from locals.

“Bend is one of the fastest growing cities in America. New people are coming in. Suddenly, they heard about us in the news,” Harding says. “We have families renting again, and people coming in the door every Friday and Saturday. And instead of a couple hundred people a week, we’re now having 1,000 people in the store a week renting.”

The last Blockbuster was seemingly operating well in early 2020, but then the pandemic threw a wrench into the economy. Per Oregon’s orders, they could stay open for curbside and in-store at limited capacity. In April they did roughly 10% of the sales they’d been doing. The Tishers cared about the staff and paid everyone their full wages, even if they weren’t working full time, though the company was losing money.

Then in May, something funny happened. Word spread that the last Blockbuster store on Earth was selling its merchandise online. Sales shot up quickly, which not only saved them from closing, but also helped the other local businesses they worked with.

“We went from having 5 or 6 orders a day to 45. Suddenly we were like, ‘we need 2,000 pairs of sweatpants,’” Harding says. “We’ve been fortunate because we have a lot of pop culture and media, and that’s helping us. I feel bad for the other small businesses that don't have that opportunity. Don’t forget to support the small business in your community.”

What’s In Store

Even as the pandemic continues to rage through the world, currently at some of its worst infection rates in the U.S., the final Blockbuster remains an unlikely success story. During a horrible year filled with overwhelming tragedy, the last Blockbuster is a feel-good story anyone can enjoy where the little guy manages to beat the odds. Even if that little guy goes by the name Blockbuster, the viewer knows it’s really the Tishers, Harding and her staff.

And since tourism isn’t possible right now, there’s maybe a lesson here to take away from the last Blockbuster: digital convenience is great, but maybe we eliminated in-person experiences prematurely.

“Our ability to do everything ourselves without social interaction took over everybody,” Harding says. “With Covid, people are starting to realize maybe that’s not such a good thing, and starting to miss things like Blockbuster, going to the theater and stuff like that. I get a lot of those comments from people when they see us: ‘I really wish we had a Blockbuster in our town.’ I think 5-10 years ago, nobody really paid attention to the local video store.”

For more information check out www.lastblockbustermovie.com.