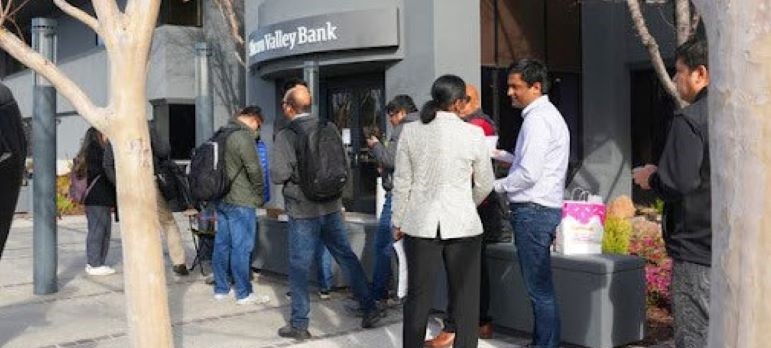

The abrupt collapse of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank threw the entire industry into turmoil and exposed fissures in the financial foundations of some smaller banks.

A month later, the nation’s biggest banks are raking in billions and will likely keep doing so even if the economy softens. But regional lenders are seen as more at risk. Deposits are falling and the cost of keeping customers is rising, eating into profits. And fears remain about the value of investments and loans, especially ones backed by real estate.

On Friday, April 21, Moody’s downgraded the ratings of 11 regional banks, citing “a deterioration in the operating environment and funding conditions.”

The downgrades came at the end of a week in which regional bank leaders, in calls with investors about their latest financial results, tried to cast the crisis as a moment that had passed. One of the banks attracting the most concern among investors, First Republic, is set to report its results today after the markets close.

Banks in California

Four of the 11 banking corporations on Moody’s list operate six subsidiary banks with offices in the Bay Area::

- Dallas-based Comerica Bank operates with 95 branches in 70 different cities and towns in California, including 30 in the Bay Area and 10 in Santa Cruz and Monterey counties.. The bank also has 336 more offices in four states. Its Entertainment Group is headquartered in Los Angeles and its Technology and Life Sciences Division is headquartered in Palo Alto.

- San Francisco-based First Republic Bank operates 20 branches in California, including 12 in the Bay Area. The bank has another 25 offices across the U.S.

- Salt Lake City-based Zions Bancorporation has subsidiary banks in California and 10 other states, including California Bank and Trust, with 13 offices in the Bay Area, and 24 elsewhere in the state.

- Phoenix-based Western Alliance Bancorporation has multiple subsidiaries operating in California: San Jose-based Bridge Capital Holdings, the holding company of Bridge Bank, with offices in San Jose, Palo Alto, Sacramento, San Diego and Fresno; Oakland-based Alta Alliance Bank with two offices in the Bay Area; Phoenix-based Western Alliance Bank, which operates 10 branches in California, including one in San Jose, and another 25 branches in five states; San Diego-based Torrey Pines Bank, with 11 offices in Southern California, plus seven other banks in three states.

Deposits are down

The runs on deposits that brought about the sudden demise of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank did not spread as widely as some feared. Still, savers seeking the perceived safety of larger institutions took their money out of many smaller banks in recent weeks.

Deposits fell roughly 1 percent, on average, at a selection of about 20 small and midsize banks that reported first-quarter earnings last week, according to analysts at UBS, who described it as “solid” given the circumstances.

In the aftermath of Silicon Valley Bank’s failure, tech clients in particular have bolted from smaller banks.

Western Alliance, an Arizona bank hit hard by the turmoil, lost more than 40 percent of its deposits from tech clients — and that was still “less than anticipated,” said Kenneth A. Vecchione, the bank’s chief executive. Overall, deposits at the bank fell by 11 percent in the first quarter, as lenders like his were “suffering from the taint of SVB’s failure,” he told analysts. But deposits then stabilized, returning to growth in the first few weeks of April, Mr. Vecchione said.

Rising interest rates a blessing and a curse

As the Fed has raised its benchmark interest rate, banks have increased the rates they charge for loans much more aggressively than what they pay out on deposits. That bolstered earnings at many banks last quarter, including PNC Financial Services, the country’s sixth-largest bank.

A so-called super regional lender based in Pittsburgh, PNC said its profit grew by nearly 20 percent in the first quarter, compared with the same period last year. But it may not last.

Those loans are financed by deposits, which are becoming more expensive. Savers are looking to money-market funds and other higher-yielding options, forcing banks to pay more to hold on to their deposits. At PNC, in the first quarter noninterest-bearing deposits fell 5 percent, while interest-bearing deposits rose 2 percent.

This trend, which is playing out across the industry, reduces profit margins and makes banks more reluctant to lend. The shift in deposits “is, for lack of a better word, ugly,” the UBS analysts noted.

“The marginal cost of funds for the U.S. banking system has just gone up a lot as a result of this flurry,” said William S. Demchak, the chief executive of PNC.

Commercial real estate

Regional banks provide the bulk of loans to the commercial real estate market, and as more attention turns to the potential risks lurking on bank balance sheets, these loans are making investors nervous. A combination of office vacancies and a coming wave of refinancings at sharply higher rates has forced many banks to set aside more money to shield against defaults.

The white-collar remote work revolution may permanently reshape the office market, bankers said. “Our office is going to be really a challenged for quite a few years, and it has a lot to do with remote work,” said Michael Morris, the chief credit officer at Zions Bancorporation, with headquarters in Salt Lake City. The bank increased its allowance for credit losses by more than 30 percent in the first quarter versus last year.

Cleveland-based KeyBank, one of the nation’s largest commercial real estate servicers, has seen what Christopher Gorman, the bank’s chief executive, described as a “huge surge” in demand for special servicing, the process for handling troubled loans. Office projects have recently eclipsed retail buildings as the biggest category of loans in special servicing, Gorman said.

Credit crunch could tip economy into a recession

Banks are tightening their lending standards, though they have cast the changes as tweaks, not a major pullback.

“We try to be the same through good times and bad, right, because what our clients value is consistency,” said Darren J. King, the chief financial officer at M&T Bank, with headquarters in Buffalo.

Still, echoing the warnings big bank leaders have been issuing, smaller banks are bracing for a downturn. Bruce Van Saun, the chief executive of Citizens Financial Group, based in Providence, R.I., said his bank was adjusting its lending decisions to account for the likelihood of “a short, shallow recession.”

Truist, the nation’s seventh-largest bank, with headquarters in Charlotte, N.C., said it was being more cautious about extending credit in what Michael Maguire, the bank’s chief financial officer, called “an increasing risk environment.”

But many said they believe the tumult set off by Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse is now in the rearview mirror.

“The waters are calmer,” said Vecchione of Western Alliance. “I like to think we did OK through this whole crisis here.”

Western Alliance was downgraded two notches by Moody’s, which cited concerns about the bank’s rising credit costs and reduced profitability.

Speaking two days earlier, Vecchione added a note of caution to his comments: “I want to be careful that I’m not like George Bush, that things are signed on the aircraft carrier that says ‘Mission Accomplished,’ right?”

Jason Karaian and Stacy Cowley are reporters with The New York Times. Copyright, 2023, The New York Times. San Jose Inside contributed information from Moody’s Investment Services.