In his first public remarks since Silicon Valley Bank collapsed, triggering widespread industry turmoil, the lender’s former chief executive pointed the finger at pretty much everybody but himself, casting blame on regulators, the media, his board of directors and even the bank’s own depositors.

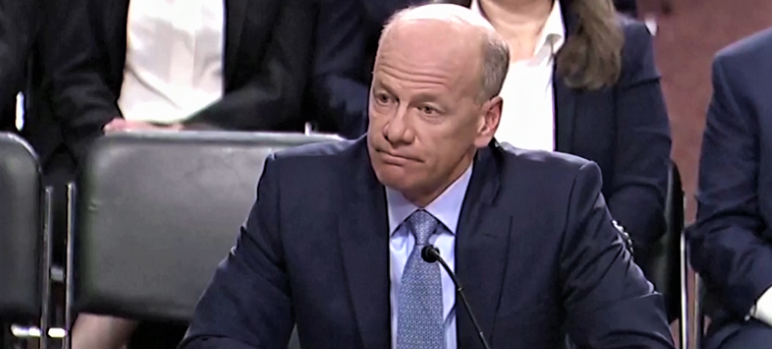

Gregory Becker, who was fired from SVB shortly after its March failure after 30 years at the bank, earned bipartisan derision on Tuesday for his explanations during testimony before the Senate Banking Committee. Although Becker repeatedly said that SVB’s unwinding was unforeseeable, senators took a sharper view of his decision making.

“It was bone-deep, down-to-the-marrow stupidity,” Sen. John Kennedy, Republican of Louisiana, told him.

Becker, who lives in Menlo Park, hadn’t publicly addressed the collapse until Tuesday’s hearing. A three-decade SVB veteran, he became chief executive in 2011 and oversaw its rapid growth in the following years.

“I worked at a place I truly loved,” he said, calling himself “truly sorry” for what happened.

SVB’s failure two months ago has prompted criticism from all corners. The San Francisco lender, with a high concentration of clients in the technology and venture capital industries, unraveled after a bank run that lasted just a few days. In its aftermath, two other lenders, Signature Bank and First Republic, also collapsed, while several other midsize banks remain subjects of serious concern among investors.

The collapse was precipitated by the bank’s decision to buy up government bonds in an era of low interest rates, particularly during the pandemic. Those bonds dropped in value when runaway inflation caused policymakers to quickly raise interest rates, making relatively low-yielding, older bonds less attractive to investors and blowing a hole in SVB’s books.

SVB also had an unusually high proportion of accounts with more than $250,000 in deposits, the cutoff to be government-insured in the event of a failure, making it particularly vulnerable to a bank run — as depositors who were worried about their cash rushed to withdraw it.

Becker said that at the time of SVB’s failure, he was working with regulators to shore up the bank. He said SVB’s large, uninsured accounts were a function of its focus on businesses and individuals whose own wealth was growing, and that because of their long history with the bank he could not have imagined they would all pull en masse.

He blamed the media for raising questions about the firm’s financial disclosures, and government officials for allowing inflation to spike to the point where rapid interest rate increases were necessary. SVB’s board, he said, chose not to hedge, or offset, the bank’s bond holdings, a move that many analysts have said would have reduced risk while dragging down the lender’s overall profitability.

Asked by one senator to identify any of his own mistakes, Becker said he had thought about the question every day for the past eight weeks, and could not come up with an answer.

“It sounds a lot like ‘my dog ate my homework,’” said Sen. Sherrod Brown, Democrat of Ohio.

The Federal Reserve, which regulates banks, last month partly blamed itself for ignoring warning signs at SVB. Its strongest criticism, however, was aimed at the bank’s leaders, including Becker, who it said took untenable financial risks to keep the lender growing quickly.

At a separate hearing Tuesday, Michael Barr, the Fed’s vice chair for supervision, said that when SVB executives found a problem with their stress testing, which simulated the impact of a crisis, they changed the test to make it less stringent, calling that “the opposite of what you’d want a bank to do” when it was facing risk.

Democrats on Capitol Hill have introduced legislation to increase bank regulation, saying the quick collapse of SVB and others was evidence that the industry requires more oversight. Some Republicans argue that the events prove the opposite: that regulations already on the books are not being effectively enforced, and that adding more would be foolhardy.

Many of the questions faced by Becker from both sides of the political aisle Tuesday involved his pay, which rose as the bank grew. He earned nearly $10 million in 2022 and cashed out millions in stock options in the weeks before the lender’s collapse. He testified that those sales were preplanned and that he wasn’t acting on any nonpublic information.

Becker and another former bank leader who testified, the Signature Bank co-founder Scott Shay, were asked if they would give back any of their bonuses, given what happened to their banks so soon afterward. Shay said he would not, calling his fallen institution a “responsibly managed bank.”

“Your opinion on what is a responsibly managed bank is now laughable,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Democrat of Massachusetts, told him.

On the topic of his bonuses, Becker said he was waiting to see if regulators would force him to return them.

“Let’s say it was legal,” asked Sen. J.D. Vance, Republican of Ohio. “Was it ethical?”

Becker declined to answer.

Rob Copeland covers Wall Street and banking for The New York Times.. Jeanna Smialek contributed reporting. Copyright 2023, The New York Times.