Edgar Salcedo, the 56-year-old owner of Ed’s Scientific Auto Body, has faced the prospect of displacement three times since he took over his dad’s business.

In the early 1990s, the colossal arena that later became the SAP Center gobbled up several of his neighbors—mechanics, welders, mom-and-pop service shops—in one of the remaining industrial wards of downtown San Jose. Years later, the regional transit authority claimed swaths of South Autumn and Montgomery streets to make way for a new light rail line.

So when investors recently began quietly snapping up parcels near Salcedo’s car repair shop two blocks east of Diridon train station, Salcedo felt a familiar unease. Then a man in a suit came calling, asking landlords and commercial tenants in the vicinity if they’d consider relocating.

“I told him, ‘No, no, no,’” Salcedo says, motioning as though waving the suit away. “I’ve told them before and told them again.”

But the second-generation business owner may not have a choice this time. Last week, the city announced the company behind the recent flurry of land buys: Google.

“I like that San Jose is growing,” Salcedo says. “It’s going to be changing—I know that. But I’m worried about what that means for my business and the people who work for me. I don’t know if we can survive a move.”

Easy Does It

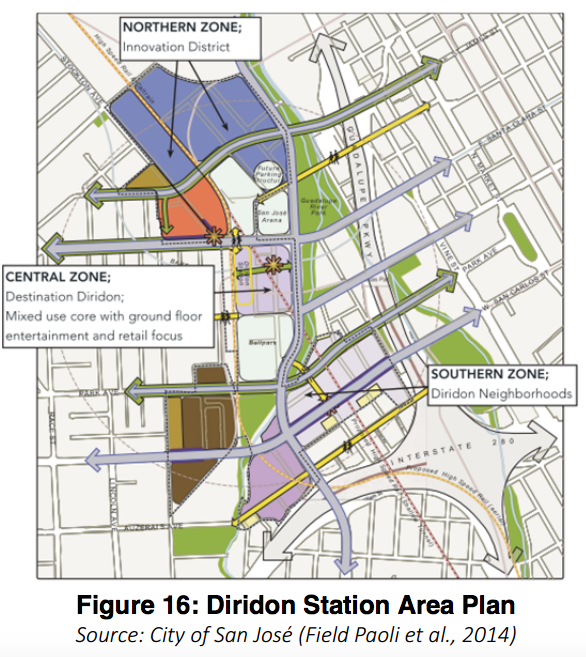

Google would radically change the landscape of downtown San Jose. The Mountain View-headquartered search giant, which plans to enter into formal negotiations with the city this month, says it wants to build up to 8 million square feet of office and research space on 245 acres near the Diridon Caltrain station.

If and when Google gets built out, which is expected to take about a decade, that would just about double the size of downtown’s office volume. All told, the project will accommodate up to 20,000 employees and thousands of new homes on land the city had long reserved for a new ballpark and the Oakland A’s.

The proposed development is a major coup for Mayor Sam Liccardo, who breathlessly welcomes the prospect of the tech giant settling into the heart the nation’s 10th largest city. Business boosters and city leaders have mused how the self-described “Capital of Silicon Valley” could finally live up to its image.

The proposed development is a major coup for Mayor Sam Liccardo, who breathlessly welcomes the prospect of the tech giant settling into the heart the nation’s 10th largest city. Business boosters and city leaders have mused how the self-described “Capital of Silicon Valley” could finally live up to its image.

“This gives us an opportunity to reimagine how Silicon Valley should build,” Liccardo says. “We’ve emerged from several decades of tilt-up campuses built in a suburban environment in a sea of parking, and what Google is looking to create is consistent with our city’s vision for how you build dense and vibrant villages.”

Scott Knies, president of the San Jose Downtown Association, says he has high hopes that Google will be a good neighbor by supporting existing businesses. Unlike Apple’s so-called spaceship in Cupertino, which is structurally isolated from the city around it, Google says it wants to keep its presence in San Jose accessible to the public. It has apparently also prompted the city to revisit the discussion about raising allowable building heights, which are partially constrained by federal limits because of the nearby airport. But there’s some leeway that Knies and city officials say could open up potentially millions more square feet to future development..

“The west side of downtown is really this Wild West of opportunity to develop a spectacular neighborhood on the doorstep of this big transit center,” Knies tells San Jose Inside. “It is forward-thinking in every manner, in its architecture and affordability, its environmental impact, with the creek that goes right through the middle of it. Then you’ve got the ability to have these public spaces. From an urbanist point of view, that is exactly what we need in downtown.”

It’s an ambitious outlook, but one that eludes the reality on the ground. Namely, that people already live and work in the shadow of the planned development.

Patty’s Inn, Kearney Pattern Works and Foundry, Borch’s Iron Works and Welding, C&C Architectural Glass and a host of light-industrial mom-and-pop establishments now face the prospect of being uprooted. Poor House Bistro, a New Orleans-themed blues venue and restaurant that owner Jay Meduri converted from his parents’ house, is another cultural landmark that lies in the path of new development.

“Google will kick us out of here,” Salcedo says. “It’s a matter of time.”

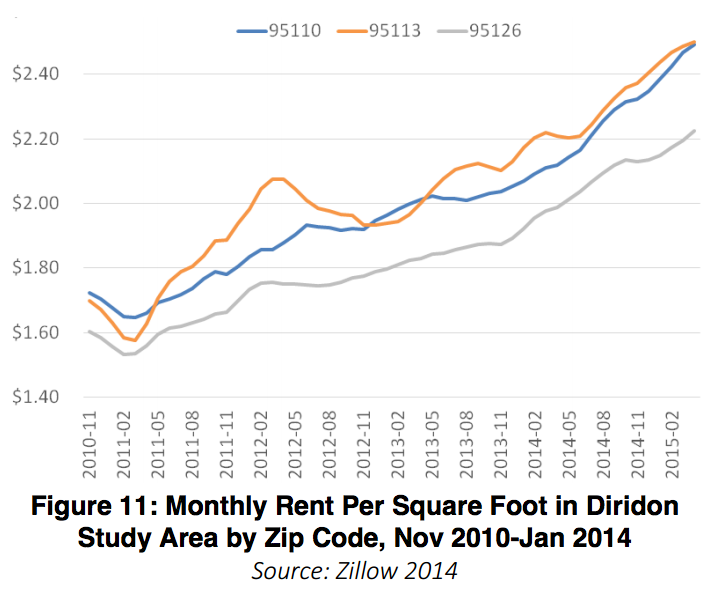

Residential tenants share those concerns. They worry that the project will drive up housing costs in a region that already claims the dubious distinction of being one of the nation’s most expensive places to live. As San Jose becomes a destination for bigger, richer corporations, the displacement of longtime inhabitants and longstanding businesses continues to outpace any attempts at protecting or creating economical housing in the city. Seeing how the affordability crisis transfigured San Francisco and now Oakland and the far East Bay, it’s understandable why people are getting defensive about Google’s planned move.

Of course, problems that plague San Jose and the rest of the region are far more abstruse than a Google complex. But the company’s economic clout should prompt serious discussion about how the city can mediate private interests and the public good, Councilman Don Rocha suggests.

“This is a great win for San Jose,” he says. “We’ve been pushing for signature projects for office and corporate development, and this might be our opportunity to finally get one. But while this strong economy is a blessing, it can also be a bit of a curse.”

Source: UC Berkeley

Researchers who study gentrification say one of the problems with the relentless pace of urban development is that it makes cities too dependent on the private sector.

State policies that limit property tax revenue have forced local governments to prioritize jobs over housing, as corporations generate more revenue for infrastructure and vital city services. The result is privately funded neighborhood revitalization—gentrification by another name—which is inherently less egalitarian than public investment.

“The neighborhoods are improved in terms of physical development and infrastructure, but the old residents are often pushed out by rising rents, and the character of the neighborhoods change,” Stanford University law professor Rich Ford says. “Small business that serve the average person—laundromats and corner stores—are replaced with more lucrative business like fancy coffee shops and high-end boutiques.”

Gentrification, Ford explained, involves revitalization that doesn’t serve the old population. Rather, it pushes them out and destroys what made a community work. The result, he adds, is that people begin to feel like strangers in their own neighborhoods.

Despite Silicon Valley’s liberal bent, policies that could help low-income residents have been considerably weaker than the influx of private capital that consumes entire neighborhoods. Like the rest of the region, San Jose has fallen woefully short of its goals for affordable housing production—just 13 percent of its projected need, according to regional planning agencies. The city banned no-cause residential evictions only this past April and lowered the rent control cap from 8 to 5 percent in 2016.

Yet even then, state policies limit the effectiveness of local displacement controls by limiting them to old housing stock. In 2011, the state Legislature also shut down redevelopment agencies, which used to generate a steady stream of affordable housing funds. No such anti-displacement measures exist for local businesses, however, which are at high risk of having to move or shut down entirely.

Denizens of the Diridon area also take issue with how they found out about Google’s arrival. Rocio Salcedo—who runs Diamond Auto Detail next door to her brother Ed’s auto body shop—says she didn’t hear about Google’s intentions until she read about it in the local newspaper.

“I’m an immigrant, I’m a business owner who pays taxes and contributes to this community,” she says. “The city should acknowledge that we’re here.”

Several city officials who spoke with San Jose Inside dismissed the notion that Google would squeeze people out. The city will negotiate the sale of 16 publicly owned parcels, according to the city, including sweeping surface parking lots and a training complex for firefighters. Other than that, the mayor assures, no rent-controlled apartments are at risk and no businesses lease the city-owned land in question.

“As far as I know, the only revered occupant who’s being displaced by Google’s arrival is the dancing pig on the Stephen’s Meat sign,” Liccardo tells San Jose Inside, referring to the iconic midcentury marquee across from Patty’s Inn on Montgomery Street. “And we will find affordable housing for it.”

The Salcedos and others who rent from warehouse owners in the area apparently have fewer resources at their disposal than the cartoon pig. Public agencies are only legally obligated to compensate people displaced from government-owned property. Tenants of private property owners, however, might receive zero help.

Deeper the Roots

Google’s proposition is undoubtedly a boon for developers who stand to profit and public agencies that stand to rake in more revenue. Nanci Klein, San Jose’s deputy director of economic development, says that by locating a massive employment center close to the most trafficked public transit hub west of the Mississippi, Google can help the region meets its goals of reducing traffic congestion.

Another selling point: the proposed Googleplex could also help San Jose bring its employment-housing ratio in line with neighboring cities.

For years, the city of a million has remained the single largest bedroom community in the United States, with far fewer jobs than working residents.

“That San Jose has less than one job per employed resident while our surrounding communities have three or more jobs for every employed resident is incredibly detrimental to us,” Klein says. “The balance is just so starkly different because we’re building housing for all those other cities. This is a chance to tip the scale. Our residents are very hungry to be able to work closer to where they live.”

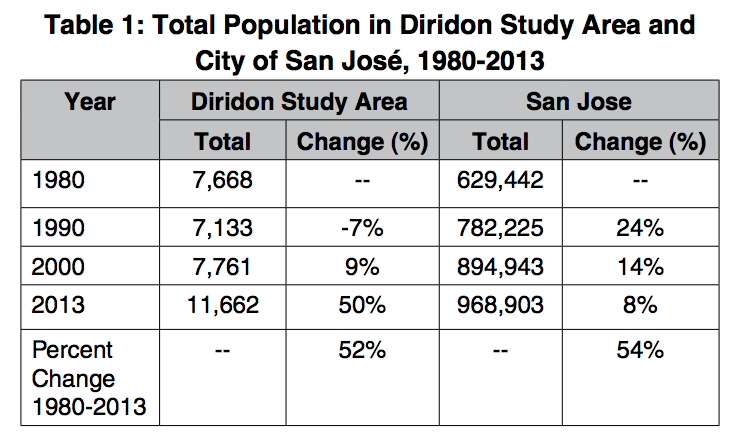

Google’s grand but incipient vision for downtown seems to complement San Jose’s Diridon Station Area Plan, which the city adopted in 2014. The downtown specific blueprint calls for significant infill that overlaps with two planned “urban villages”—essentially clusters of housing near jobs and linked by public transit. The Association of Bay Area Governments and the Metropolitan Transportation Commission—well-funded regional planning agencies—require cities to adopt “smart growth” plans, also called urban infill, as a way to prevent more suburban sprawl. But the strategies largely fail to account for displacement.

After years of gradually translating that vision into reality, the area around Diridon station is shaping into an upscale urban hamlet. A 2015 report by the University of California, Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project called the Diridon area one of the most susceptible in the Bay Area to displacement.

After years of gradually translating that vision into reality, the area around Diridon station is shaping into an upscale urban hamlet. A 2015 report by the University of California, Berkeley’s Urban Displacement Project called the Diridon area one of the most susceptible in the Bay Area to displacement.

Development in the 1980s pushed out low-income families and galvanized the neighborhood for today’s explosive growth, according to the report’s authors, Karen Chapple and Miriam Zuk. When the Diridon Station Area plan was announced three years ago, activists renewed the call for affordable housing, which the city funds by charging developers two separate fees to make sure that 15 percent of all new housing remains affordable to low-wage earners.

Before the city adopted the lofty plan, Councilman Rocha and others pushed for anti-displacement strategies.

“I am mindful that while high-tech clusters and impressive architecture may be necessary components for a great city, they are not the only components,” Rocha wrote in a 2014 memo urging his colleagues to at least give some teeth to the affordable housing component. “An iconic station building will need janitors to clean the floors. Knowledge workers will need teachers to educate their kids. An entertainment zone needs waiters and a stadium needs ushers. The stations and stadiums, the prestigious tech companies—all will rely, at least in part, on the labor of people who do unglamorous work for modest pay and spend a good portion of their income on just getting by. I believe there should be some consideration in our plan for them.”

The recommendations Rocha made were ultimately adopted, but he believes more policy tools could and should be available. Last year, the second-term councilman pushed for a commercial linkage fee, which would have accrued more money for below-market-rate housing. Mayor Liccardo and his business-friendly allies rejected the proposal and the council declined to even study the possibility.

“To not even act at all was ... a major, major failure,” Rocha says. “These are examples of opportunities lost that could have been available to us as we work with Google.”

Professor Ford says cities grappling with displacement can protect businesses with deep roots in the community by securing long-term leases or partnering with nonprofits to keep their costs down. Knies, the downtown association chief, says that bigger tech companies can do their part by subcontracting with local businesses.

“We’re in a position to make Google compensate the public for their impact,” says Sandy Perry, head of the grassroots Affordable Housing Network of Silicon Valley. “We need to make sure that they buy into their end of the social contract.”

Liccardo says cities always struggle to know how much to regulate private investment and at what point those regulations drive developers to neighboring towns.

“Nobody knows where the line is until you start to notice that folks aren’t coming your way anymore,” he explains, noting that the city learned its lesson the hard way by imposing traffic impact fees that discouraged development in north San Jose. He added: “There’s a very clear lesson to us … you’re not going to have 200 developers come down to protest the imposition of a new fee. The way that they will express their dissatisfaction is with their feet.”

But Liccardo says he’ll make sure Google pays its fair share.

“We’re not cutting them any deals,” the mayor says.

The neighborhood around the Diridon train station has already experienced significant displacement over the years. (Photo by Greg Ramar)

> Will Downtown Ever Be the Same?

10 million square feet of new office space?

“Downtown” will NOT be the same.

For now googles “Plan” isn’t even that. It’s a thought, and one we have to very carefully consider.

It’s well known that google provides services to employees to keep them in a gilded cage. They don’t have to leave for meals, as these are provided by google. They have laundry services. They pretty much provide every service that a city might provide.

So we aren’t going to get that sought after “lunchtime tax revenue” What we will get is a huge campus, lots of cars and google busses coming in and out every day. Mostly cars though. Nobody has ever provided ridership numbers on google busses, but from friends that work at google, barely anybody rides them. You might see 10 people max on a Gbus at any given time.

We’re going to add the same traffic major events have at the shark tank on a daily basis… Twice a day.

While I appreciate googles “thought” here, I don’t see how the campus is going to “revitalize” downtown. It’s about a mile outside of the DTSJ core. There are other areas of San Jose that would be a better fit for this many people. South San Jose, Santa Teresa are areas that have been trying to revitalize businesses for some time now, and have the 2.8m sqft to accomidate them. There’s LRT and Caltrain available.

What I’m banking on is that the commute will persuade Googlers to move nearby downtown and decrease their commute. Then, if shopping and services grow, it will really become more vibrant and develop its character. I think of how San Diego’s downtown grew from nothing and is now an incredibly exciting center for SD. I hope the same happens to SJ’s downtown.

The development of San Diego’s downtown was facilitated by what the Kroll Report (2006) described as unsound governance, falsified financial reporting, conflict of interest, planned underfunding of municipal obligations, and the generalized “failure of gatekeepers.” San Diego was confronting bankruptcy several years prior to the mortgage meltdown and its residents are still on the hook for billions in debt.

That said, I think the private developers did pretty good for themselves.

I’m a vendor/contractor sitting on an 85% filled Gbus that takes me 50+ miles from my residence to Soulless Silicon Valley so you’re clearly wrong about that “fact”. It’s a guarantee that ridership numbers are available as that’s what drives the routing for this Data Geek company in the first place, so again, you’re wrong about that or you’re simply not asking the right questions of the right people.

“WE ARE THE GOOGLE , YOU WILL BE ASSIMILATED , RESISTANCE IS FUTILE , THE LITTLE ONE’S WILL BE EATEN , RESISTANCE IS FUTILE ! RESISTANCE IS FUTILE ! RESISTANCE IS FUTILE ! YOU WILL BE EATEN IF YOU RESIST ! THE COLLECTIVE IS ONE, YOU WILL BE ASSIMILATED ! …………………WE ARE THE GOOGLE !

These small town san jose politicians are so far in over their heads.

Google will be added to a select list of groups so special that they are afforded representation by local government. They will join the gays, transgenders, illegal aliens, renters, and the homeless as the only people in San Jose who are visible to our politicians.

Oh no, not “the gays!” If Google replaces racist old cranky homophobes, good.

> If Google replaces racist old cranky homophobes, good.

So, if Google replaces racist old cranky homophobes with tribalist young snotty heterophobes, how does society benefit? I don’t get it.

The traffic will be wonderful. Just think San Jose can’t even manage timing their traffic lights; something most major cities get right off and these guys have had 30 years.

NO. google has played a huge part in this area exploding with people and housing values. I was born here, raised here, I’m almost 40 and work as a chef.. I can barely afford a one bedroom apartment, with my fiancé of ten years — yes, 10, we cant afford a wedding.

No to San Jose Google.

Fix the freeways and the traffic first. jfc.

What, you don’t want to move up to making chicken caesar salad in a box for people stuck in the GOOGLE Ghetto?

You’ll make millions and can be married in the front lobby, or better yet in an online virtual wedding!

FIX THE TRAFFIC CONGESTION FIRST!!!!!!! IM so pissed there are bus lanes added on alum rock, I see maybe one or two busses using that exclusive lane while busses are still allowed to use the regular lanes as well. But what do i Know? Im just a peasant.

The Diridon Station area is a perfect area for development of jobs and transit oriented housing. Right now the whole neighborhood is a blighted eyesore. I’m not saying Google’s plan is bad or good, but I don’t see the benefit of preserving what’s there now for the sake of a few mom and pop businesses.

conflict of interest, planned underfunding of municipal obligations, and the generalized “failure of gatekeepers.”