Before Kathy Kwan lavished a $225,000 gift on the San Francisco AIDS Foundation, she took a tour of one of the nonprofit’s clinics. What the Silicon Valley philanthropist saw inside—homeless, drug-addled, disease-ravaged clients, a panorama of human suffering—made her want to run out the door.

“The only thing that saved me from turning away was that the director of the foundation used to sit next to me in grad school,” says Kwan, who, a decade ago, formed a multi-million dollar charitable foundation with her husband, Alan Eustace, Google’s former vice president of Knowledge. “One of the challenges for a philanthropist who’s just starting out is that it can be really hard to empathize. You’re meeting a population of people and you’re in a low-income environment that you may never have encountered. It’s a culture shock.”

Not a lot of philanthropists talk about philanthropy, let alone with such candor. But Kwan speaks openly about how her foray into the world of charitable giving has forced her to grapple with her own biases.

“We live in such geographic pockets from block to block that we often don’t realize how much need there is in our own community,” says the mother of two and Menlo Park resident. “There’s a discomfort in acknowledging that we have all these problems close to home. It’s a lot harder when the problem is local.”

A new report calls it the empathy gap.

While Silicon Valley’s affluence and charitable giving has exploded, the report found that region’s income inequality rivals that of the poorest nations and its philanthropy is directed just about everywhere else but in its own backyard. The study, titled “The Giving Code” and published last month by consulting group Open Impact, found that only about 7 percent of all giving by private foundations in San Mateo and Santa Clara counties goes to local nonprofits. That’s $94 million out of a total of $1.2 billion. Only 3 percent went to nonprofits that are not only based locally but also dedicated to addressing local needs. The proportion of corporate charity donated to local organizations actually fell by a couple percentage points from 2006 to 2013, even though overall giving increased four-and-a-half times in that same timeframe.

Part of the disconnect may stem from the fact that many Silicon Valley philanthropists aren’t from the Bay Area and lack connections to local issues. They also tend to support causes they’re familiar with: schools, hospitals, conservation.

“There’s a learning curve,” says Kwan, a South Bay native who makes a point of focusing her giving close to home. “I’m like a lot of philanthropists in that we were really fortunate to come into some wealth. But you don’t really realize that you’ll have to give away these large sums of money, which usually starts out as a tax event, and you don’t really know where to start. I can tell you that the first people who come to your doorstep are from your children’s school, then your university.”

The report’s authors, Alexa Cortes Culwell and Heather McLeod Grant, explain the shift in giving—from local to global—as a reflection of corporate values. Through interviews with 300 donors and nonprofit leaders, they determined that private charitable foundations want to support organizations that align with the business goals of the philanthropists. The “giving code” referenced in the study’s title refers to an unspoken ethic that emphasizes metrics and results over altruism and moral obligation.

Call it philanthro-capitalism. The Economist coined the term in 2006 to describe an emerging idea that “social investors” set out to “do well by doing good.”

It was in the spirit of philanthro-capitalism that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan vowed last year to donate 99 percent of their shares in the social media giant—worth $45 billion—to charity during their lifetime. By way of an open letter to their newborn child, they announced the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, a limited liability corporation dedicated to “advancing human potential and promoting equality” through “philanthropic, public advocacy and other activities for the public good.”

News of Zuckerberg’s foray into philanthropy was met with adulation. “By all means, let us praise Zuckerberg and Chan for their generosity,” the New Yorker wrote. “And let us also salute [Microsoft founder Bill] Gates, who started the trend.”

Nearly drowned out by the applause were plenty of critics, who pointed out that the purported charity had more to do with cash management and laying fertile ground for future business opportunities than anything else. Jesse Eisinger, a reporter for investigative journalism nonprofit ProPublica, described the formation of a limited liability company as simply a way to move money “from one pocket to the other.” Zuckerberg channeled his philanthropic capital through the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. As a donor-advised fund, the foundation offers an immediate tax deduction with no requirement for charity, according to the Internal Revenue Service.

As a corporation instead of a traditionally tax-exempt nonprofit, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative can freely invest billions into political lobbying. Or, to borrow language from the initiative’s mission statement, “participating in policy debates.” The Facebook founder has already used his purportedly charitable investment vehicle to fund for-profit private charter schools.

“Instead of lavishing praise on Mr. Zuckerberg … this should be an occasion to mull what kind of society we want to live in,” Eisinger wrote. “The point is that we are turning into a society of oligarchs.”

The “Giving Code,” for its part, describes philanthro-capitalism more diplomatically than Eisinger and never actually uses the term. Because Silicon Valley philanthropists view social change in terms of investment, the report notes, they tend to speak a different language than community-based organizations that focus on human services such as feeding the hungry and housing the homeless.

“In talking about the world and about their work, most nonprofit leaders speak a kind of moral language that emphasizes social responsibility, social justice, equity and the common good,” Culwell and Grant find. “Many have backgrounds in social work or other similar fields and use shorthand jargon—words like ‘empower,’ ‘transformation’ and ‘theory of change.’”

Donors, on the other hand, describe charity in more utilitarian terms. Instead of transformation, they talk about getting the “biggest bang for the buck.” Instead of empowerment, they talk about “capacity building.”

“Theirs is a language of finance, of metrics, of power, of capitalism, of winners and losers,” according to Culwell and Grant. “And it is starkly different from the more personal and emotional language that nonprofit leaders use to convey both the impact of their work and the vital human needs that drive it.”

The “Giving Code” puts into words what Kwan says she felt all along: that there’s a language barrier between the nonprofit world and her own.

“When you talk about social justice, you’re implying that there’s a wrong being done in society that we need to fix,” she says. “I like to think in terms of opportunity. I come in saying, ‘Let’s create opportunities for people who don’t have as much.’ I want to figure out how to create excitement about a cause and build it up from there.”

The Silicon Valley Community Foundation has grown to one of the largest charitable funds in the nation with $7 billion in assets by mastering the aspirational vernacular preferred by Kwan and her class of big-money philanthropists.

“As anyone in sales knows, you have to use the language of your customer,” says Emmett Carson, CEO of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation. “Giving is individual, giving is personal, and the way we attract givers is by showing how their resources can make a difference. It’s a marketplace of ideas.”

Carson takes issue with the way the report focused on philanthropy within a two-county boundary, however. Most of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation’s donations go to the nine-county Bay Area, he says. He invites people to peruse the organization's online database of grants (available here), which shows where donors sent their money in 2015.

“The study by definition creates boundaries that, to me, are inconsistent to how we operate,” he says. “People live regionally, and their giving patterns reflect that.”

This relatively recent shift from conventional charity toward “social investment” and “social impact” arguably renders philanthropy yet another tool to diminish taxes and manage wealth. But the new breed of charity tend to eschew discussions about how to reform a system that perpetuates the kind of inequities that afforded them enormous wealth in the first place.

In his 2012 book, The Great Divergence, labor policy journalist Timothy Noah concluded that U.S. taxes redistribute income far less equitably than other developed nations. According to the Congressional Budget Office, all federal taxes on the top 0.01 percent fell from 59 percent in 1979 to 35 percent in 2004. UC Berkeley economic Gabriel Zucman identifies offshore tax havens as another source of income inequality. In his new book, The Hidden Wealth of Nations, Zucman estimates that at least 8 percent of the world’s wealth and 4 percent of American wealth lies in tax havens.

“Many Silicon Valley billionaires pay negligible taxes,” Zucman tells San Jose Inside. “If they are serious about social progress, they should start by paying what they're supposed to. Their attitude can be summarized, in a nutshell, as saying: ‘Please allow me not to pay too much taxes, I’ll give my wealth to what I think are valuable causes.’ But if billionaires are free to choose how they contribute to society, many people will ask, ‘Why shouldn’t I? Why do I have to pay taxes?’ So in the end, tax-avoiding philantro-capitalists end up harming our social contract and the very goals they claim to be pursuing.”

In his book, he adds: “Nothing in the logic of free exchange justifies this theft.”

But questions of policy and politics lie beyond the ken of much of the nonprofit world, which deals with immediate crises of human need. Still, for nonprofits helping clients with subsistence-level needs, it can be hard to view the world through anything but a lens of social justice. Statistics on the stagnant wages and the rising cost of living point to systemic inequities that call for sweeping structural change.

The “Giving Code” puts into numbers what South Bay nonprofits have grappled with for years. Skyrocketing housing costs have heightened demand for services, but funding for charities that provide them has been on the decline. More than half the community-based nonprofits interviewed by Open Impact say they can’t keep up. All too often, that means turning people away. Shelters for runaways, domestic violence victims and the homeless run out of room. Food pantries run out of food.

Second Harvest Food Bank, which feeds 253,000 families a month in Santa Clara and San Mateo counties, will have to cut services for hundreds of families a month because of a precipitous drop in donations this holiday season. The amount raised this fall compared to the same time last year is down by $1.9 million, according to the nonprofit. The number of gifts and givers is down by about 2,100 and 1,700, respectively.

“This is your worst nightmare as a nonprofit,” Second Harvest CEO Kathy Jackson says.

Call it, as Culwell and Grant do, the prosperity paradox—one that won’t be cracked without rewriting the so-called giving code.

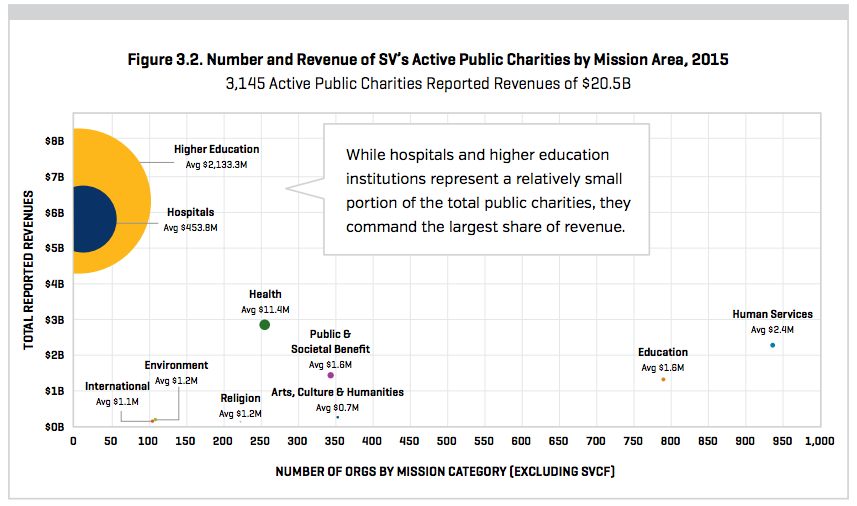

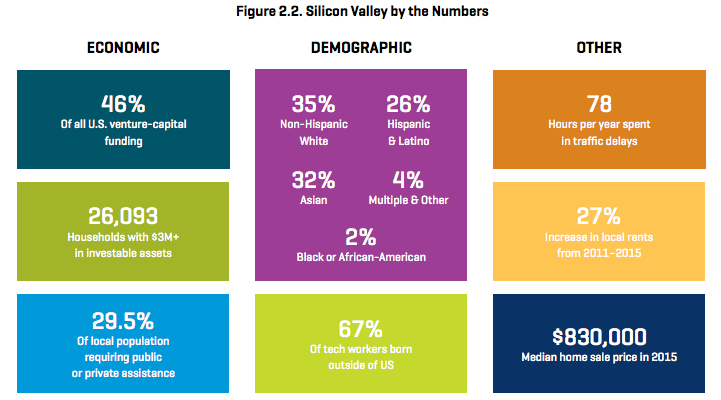

In 2015, the 150 biggest publicly traded Bay Area tech companies generated $833 billion in sales. The number of so-called “unicorns”—companies valued at $1 billion or more—grew from three in 2011 to 21 this year. According to Joint Venture Silicon Valley, the region is now home to 76,000 millionaires and billionaires and 50,000 households with $1 million or more in investable assets.

The creation of enormous wealth has deepened existing inequalities, the report points out. Rising housing costs have forced a growing number of the South Bay’s 2 million denizens into dire financial straits. Nearly a third of residents in San Mateo and Santa Clara counties (800,000 out of 2.6 million) rely on some form of charity or public welfare to get by, according to Joint Venture. Middle-class jobs are on the decline, shrinking by 3 percent over the past decade. From 1989 to 2014, the middle-class has contracted by 11 percent in Santa Clara Valley and 10 percent along the Peninsula. People who moved to the Central Valley, East Bay or South County for a cheaper place to live have to sit in traffic snarls that grow worse as the affordability crisis persists.

Yet most of the giving to nonprofits that serve local needs, such as Second Harvest Food Bank, come from low-income or middle-class donors—many of whom relied on the charity themselves. Sixty-five percent of donations to Second Harvest come in the form of small gifts from local individuals, Jackson says. At donation drives, she adds, a big share of the volunteers come from families that still depend on the food bank.

“I know what that’s like, to worry about how you’re going to feed your family,” says Patrick Manigque, who relied on Second Harvest to feed his young daughter and cancer-sick wife. “So I would volunteer to help when I could.”

That people who earn less are relatively more generous holds true on a national scale, according to UC Berkeley psychologist Paul Piff, who published a report in 2011 on the giving habits of different social classes. Americans in the bottom 20 percent of the income pyramid gave 2.3 percent of their earnings to charity. The richest 20 percent, on the other hand, gave just 1.3 percent. Unlike their wealthier counterparts, many low-income donors cannot claim tax deductions because they eschew itemizing charitable gifts on their tax returns.

But what reforms would make it so that we don’t have to relegate sustenance, medical care and other basic human needs to charity?

“If we only knew,” Jackson says. “I’d love to be out of a job if that means the need is met.”

The Silicon Valley and the South Bay need a non-profit like the Chronicle’s Season of Sharing (www.seasonofsharingDOTcom). Season of Sharing is a “100 Model” charity. (“100% Model” charities have a separate endowment to cover their expenses so that 100% of public donations go directly to project funding). In the case of Season of Sharing, all expenses are covered by the SF Chronicle and the Haas Family Foundation.

Pretty simple proposal: We get the South Bay Silicon Valley Titans to work together to underwrite such an effort. A South Bay version of Season of Sharing could do a lot of good!

Perhaps they can take a look at the generosity of the “Clinton Foundation and Global Initiative” for inspiration.

No wait forget that, they only donate 10% and the rest is administration and expenses.

How about donating it to the Salvation Army, it works all year round.

> It was in the spirit of philanthro-capitalism that Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan vowed last year to donate 99 percent of their shares . . . .

So, Jennifer, if you don’t like “philanthro-capitalism”, what is your preferred alternative?

How about state socialism? The government distributes resources to all the people fairly. Or, at least the 40% that it doesn’t steal and divert to the “Court Economy”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pKYBu9xIfac

Now I understand why the dear leader is so dear, if you’re good you get a cheap condo and a gold machine gun to kill yourself with!

I couldn’t help noticing the shocking absence of diversity in North Korea.

How can they be good progressives without multi-culturalism?

Have any San Jose Councilmembers announced cultural exchange visits to North Korea? Does San Jose have a sister city relationship with Pyongyang or Inchon?

Jennifer Wadsworth, nice job.

Inchon is in South Korea, not North. They are already sister city with Burbank, CA. So I doubt they would be interested in another one in California.

North Korea does have a decent size of Jurchen(aka Manchurian) minorities among others.

A few points here: The San Jose Mercury News has the annual Wishbook, similar to the SF Season of Sharing. Second, while I believe in local giving as well, I do consider “bang for the buck” as who wouldn’t want to see their money do the most good? That’s why Heifer International is so compelling, because you provide animals that reproduce and enable people to be self sustaining and lift their own standard of living and they are required to pay it forward by providing offspring animals to others. It is a gift that keeps on giving vs. a bag of groceries that are consumed once and don’t really provide a hand up to a higher standard of living.

I think the saying is,

“Give a man a fish and he will eat for a day.”

“Teach a man to fish and he will eat for a lifetime.”

> That’s why Heifer International is so compelling, because you provide animals that reproduce and enable people to be self sustaining and lift their own standard of living and they are required to pay it forward by providing offspring animals to others.

I love it!

But if this idea ever took off, it might end up looking like capitalism. Are you sure this is legal in California?