Emergencies don’t come cheap.

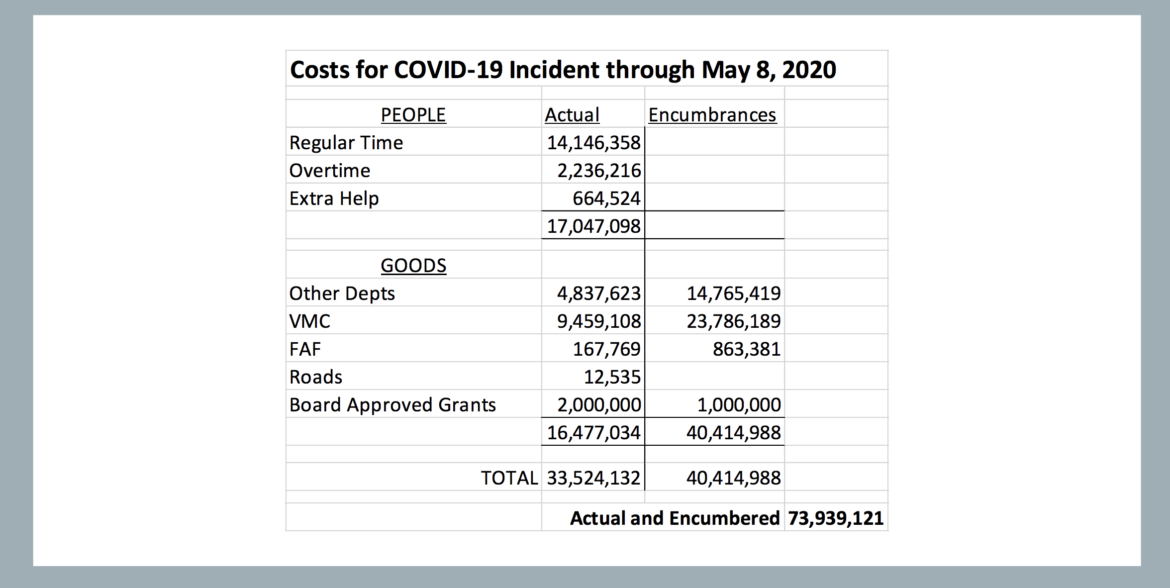

Over the past few months, Santa Clara County has spent $74 million—and counting—to tackle the pandemic, snapping up masks, gloves, gowns and sanitizer at a frenetic pace.

Beyond verbal reports in public hearings about broad categories of expenditures, however, where that money’s gone, exactly, remains unclear.

Once the Board of Supervisors declared the COVID-19 outbreak an emergency, it expanded County Executive Jeff Smith’s authority and suspended competitive-bidding standards that typically govern public purchasing.

As soon as the Feb. 10 order came down, Theresa Therilus, the county’s chief procurement officer, went about scouring a hyper-competitive market and splintered supply chains for resources needed to save lives.

“In this crisis, things go very quickly,” she explained during a rare pause this past weekend. “If you’re a day late or even a few hours behind in reaching out and finalizing an order, you might lose it and that can mean you don’t have the supplies that you need.”

But as panic ebbs to vigilance and the curve flattens, demands for transparency have begun to mount. More than three months into the officially declared public health emergency, the county has yet to disclose much about its exigency spending.

To shine some light on the mystery budget, supervisors Susan Ellenberg and Dave Cortese today unveiled a proposal to create a publicly viewable county COVID-19 cost tracker. The online dashboard would list expenses by department, board policy, vendor and eligibility for state or federal reimbursement.

“Those details are essential,” says Ellenberg, who began calling for a line-by-line breakdown crisis spending in early April. “My colleagues and I are being asked to make really significant decisions about which services to cut and which to keep. … We need this information faster because of the gravity and scope of the decisions we have to make.”

As does the public.

“We are asking our community to sacrifice so much right now,” she said about the reasoning behind the referral. “So, I think we owe it to them to show that we’re spending this money in a way that is going to get us out of this crisis.”

Constituents should know how much the county’s investing in benchmarks that health officials set as conditions of easing restrictions, Ellenberg added. Namely, that hospitals have enough surge capacity, testing is widely available, contact tracers can track and isolate cases to curb outbreaks and that we see a two-week dip in COVID-19 diagnoses.

The concern isn’t necessarily even that the county’s overspending or falling prey to the kind of price-gouging and fraud endemic to states of emergency.

“I’d also like to know if we’re spending enough,” the D4 supervisor said.

While other jurisdictions have started looping in the public about emergency spending, Santa Clara County officials say they’ve been hampered by quotidian obstacles. Chief among them: the way COVID-19 expenses get logged in a database.

When county Budget Director Greg Iturria presented the $74 million figure at the May 12 board meeting, he said that was as much detail as he had at the time. In a phone call days later, he described how the hold-up comes down to the way the county flags expenditures using two main identifiers in two separate accounting systems.

“What we’re working on now is going back to everything under those codes to determine whether it’s a reimbursable by FEMA or the coronavirus relief package,” he said, “and that’s going to take us a long time.”

It’s critical for the county to get it right, he said, because by the time the feds get around to auditing the records years later, some of the documentation might be missing.

For now, the most granular data available on the COVID budget rests under the purview of county Controller-Treasurer Alan Minato. But even he doesn’t have a clear view yet.

“Basically, we can see what vendors have been paid but not what we spent the money on,” he said in a phone call Monday. “For example, I can see we got a vendor here, Granger, but until I drill down and look at that invoice, I can’t tell what we bought from them.”

Multiply that hurdle by thousands of line items across dozens of county departments and the scale of the data-gathering becomes clear. “We want to be transparent about this,” he said. “In fact, I’m working on coming up with that data right now.”

In hindsight, the treasurer said he should have been prepared for this kind of crisis.

“You know, I can say that’s my fault,” Minato said. “If I had to do it all over again, I would have set up the coding up front.”

Most emergencies—earthquakes, floods, rolling blackouts, you name it—have a clear ending and some kind of lingering, but dissipating, fallout. That makes it easier for money handlers like Minato to determine when to start going back to catalogue urgency spending. In this event, he said, the timeframe is less fixed.

“We’re months into this, and there’s no end in sight,” he said. “But we have started working on this—it’s just taking longer because this is an ongoing emergency.”

Fellow department heads echoed that point. The protracted nature of the crisis is the single most complicating factor, Therilus said, noting that she’s led procurement teams through various emergencies before, including hurricanes in Florida.

“Generally, in an emergency, you have a finite end and then you’re dealing with the aftermath,” she said. “Of course, some principles stay the same: good communication, organizing between parties and departments, that kind of thing. But in this case, I think there’s a level of additional stress in managing the unknown and the fact that we’re still responding in real time.”

Though some of the rules have changed for the time being, Therilus said her department is doing its due diligence in vetting vendors and ensuring that money is wisely spent.

Supervisor Joe Simitian, who sits on a hospital and healthcare subcommittee, said he applauds calls from his colleagues for more clarity.

“That transparency has to be there,” he said. “I think right now, understandably, everyone’s focused on saving lives and putting people back to work. But long term, we have to have a better sense of how we’re managing taxpayer money.”

The budget-dashboard proposal put forth by Cortese and Ellenberg today comes up for debate at next week’s board meeting. In the meantime, Minato said Smith has already assigned him to prepare all the data demanded by supervisors. As for this news outlet’s request for some of the same, that will have to wait.

“You’ll have that information as soon as it’s available to the public,” Minato assured in a follow-up phone call today. “My staff will run that, but right now they have to respond to the board, which is going to take me all week.”

> The budget-dashboard proposal put forth by Cortese and Ellenberg today comes up for debate at next week’s board meeting.

ABSOLUTELY! This is a no-brainer.

OF COURSE THERE SHOULD BE A SPENDING DASHBOARD!

I probably should take back some of the mean things I’v said about Cortese, but not just yet.

I’ll hold off and wait for more evidence of common sense.

And, as long as they’re making another dashboard, they need to make an economic and social impact dashboard:

— number of jobs lost

— number of businesses closed

— number of suicides

— reduction in county business activity

— loss of tax revenues

— loss of student school days

Last recession local city employees made major concessions in pensions. Paying more in and receiving less. It was a good move. However Santa Clara County employees did not. I would like to see them even out their pension to reflect what other cities are providing. Do you think any of the supervisors have the guts to bring this up?

In addition to the detailed spending, there should be detailed information about whom has actually benefited from this spending. For example, Latinos, Blacks, and at risk worjers were turned away at local county clinics when they requested testing. This after being exposed to someone who tested positive for the virus. At the Tully clinic, Latinos who requested testing after being exposed were told the tests were for health workers. All this while Ash Kalra was informing his friends and supporters where to go to be tested. It is not only important to know how all this money was spent but on whom too. Why is Google and Apple benefiting from this testing? Why people cannot be tested at their providers’ place not at sites run by Google and Apple? STATE AUDIT ON SANTA CLARA COUNTY NOW!

So now, this is the Dollar Dave I actually what to see. SHOW US HOW OUR TAXS DOLLARS HAVE BEEN SPENT! DOLLAR DAVE 2020…I am thinking I may vote for him if he gets this right.

Theresa Therilus can’t manage one order much less explain any of the excessive spending under her watch. She did nothing to connect with Asians or Latinos in Santa Clara County.

No wonder she fled back to Florida to be manager of a town with a rich history of corruption that has plagued the 65,000 residents. Current budget shortfall is $25 million and climbing. My money says she doesn’t last a year in North Miami.

Miami Dade has officially left the building!

If you get bored while sheltering in place grab some popcorn and check out the North Miami Government meetings.

https://livestream.com/cityofnorthmiami/events/9265960