The letters were simple at first, innocent and inquisitive. “Hi daddy, how you been? I hope you’re doing well in prison,” Angela Birts would pencil in on blue-lined binder paper. She was nine when her father, Willard Birts Jr., got locked up for good—his third strike after several priors for possession and burglary. A life sentence.

“I’m doing fine,” he’d reply, masking anger over his fate. “Proud of you.”

As Angela grew, so did the depth of their correspondence, from a few questions in crayon to reams of frank, confessional missives. The poor girl from East Palo Alto told him how she earned a scholarship to Menlo School, the private academy for Silicon Valley’s millionaire progeny. She wrote about how she took two bus routes every weekday to go from the three-bedroom apartment she shared with her seven step-siblings and her mom to the manicured campus in Atherton.

She wrote about being one of a few black students on a mostly white campus. Her father understood. He was once one of a handful of African Americans at a similarly homogenous high school in Mountain View. He sent her a paperback copy of “Warriors Don’t Cry,” the autobiography of one of the first black pupils to attend an all-white school in the 1950s segregated south.

“I didn’t know he could relate to my situation,” Angela says. “But that’s how it was—when I shared something about myself, I learned something about him, too.”

Angela wrote about how the family fared. She pen palled about boy troubles and her father would remind her to stay focused. “Don’t fall for a boy like I was around that age,” he said, reminding her of his sentence and her uncle in San Quentin.

Angela mailed hundreds of photos so her dad could see her grow. He traded commissary goods to get another inmate to sketch portraits of some snapshots and send them back.

“Little gifts for her birthday,” Willard says. “I couldn’t offer much else.”

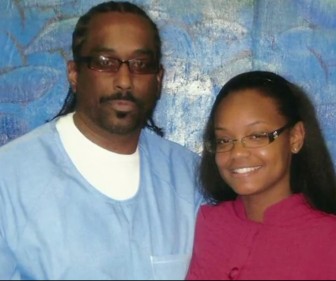

- Willard and Angela during a prison visit.

From a distance, he watched her come full circle, earn a master’s from Stanford and take a job as diversity coordinator at Menlo School. She mentors students at the same campus she attended, dealing with some of the same struggles she’d faced as a teen.

Meanwhile, Angela saw her dad become a scholar in his own right. Confined by concrete walls, Willard read voraciously and learned about politics, history, the American legal system, religion and philosophy. He came to terms with his sentence but held out hope he might someday take Angela, now 28, out for lunch. He dreamed of attending college, starting his own business. If he got out, he could become independent. Just like his little girl.

Thanks to the passage of Prop. 36 in 2012, a law that allowed non-violent “Three Strikes” convicts to appeal their sentence, Willard got his shot at freedom. It was up to his public defender, J.J. Kapp, to persuade a panel of prosecutors that it was in the community’s best interest to let him out. He had to prove that Willard would thrive outside of prison, that he had a support network and, most of all, that he had Angela.

“But it’s hard to convey that in a written statement,” Kapp says. “We don’t even get to present to the panel.”

The deputy public defender teamed up with the Albert Cobarrubias Justice Project, a grassroots legal reform group, to capture Willard’s story in video. The Justice Project had been compiling scrapbook-style biographies of defendants in criminal cases for years to push for reduced sentencing. A few years ago, the effort evolved to include minutes-long videos, taking the viewer to the defendant’s living room, their workplace and to their families.

“The video was a way to bring the presentation to life and feature the unique relationship between Angela and Willard, which I thought could anticipate success for this case,” Kapp says. “It turned out to be exactly that.”

For Willard, the video spanned less than seven minutes, all of Angela making a case for him. “I will say that as I’m getting older it’s almost like I need him more, so him being incarcerated is getting harder and harder and harder,” she told the camera. “Although he has been incarcerated, that didn’t really stop him from being a good father to me.”

Though rare, the documentary-style social biographies are catching on among public defenders. They first appeared in the mid-’90s but gained momentum with the advent of cheaper recording devices. Attorneys use them in the sentencing phase but also after, as in some of the Three Strikes hearings in Santa Clara County. Elsewhere in the country, private firms charge up to $20,000 for a longer, polished documentary of the person’s life.

Locally, Raj Jayadev and his team for the Justice Project produce them for attorneys for a nominal fee. Since rolling out the program a few years ago, they’ve helped beat two life sentences, stop a deportation, turn a one-year jail sentence into community service hours, cut a 15-year sentence in half, slashed nine years off another sentence and prevented a teen from getting tried as an adult. More cases are pending and Jayadev’s team is traveling the country giving talks to legal professionals interested in creating video leniency appeals of their own.

“These (videos) are based on a belief system about families and how it’s through families we can reform the criminal justice system,” he says.

Public defender Melissa Wardlaw calls the videos “a revelation.”

“When you’re talking about community good and community safety, it’s a very complex problem,” she says. “People don’t commit these crimes in a vacuum. There were circumstances we don’t know about. Then again, it’s not just about showing a video of a crying mother, because almost everyone has a crying mother. It’s about delving deeper into their story.”

Critics of the videos argue that they offer an edited take on the defendant’s story and that prosecutors don’t have a chance to offer a counter-narrative or interview the filmed witnesses. But several local defense attorneys are sympathetic. The mini-documentaries give both sides a better sense of the personalities and struggles at play.

- Willard meets with his public defender, J.J. Kapp, days after his release.

Kapp, a young trial attorney when he lost Willard’s case in 1997, had a head of silver-white hair when he visited his former client in Solano State Prison a year-and-a-half ago. Both were choked with emotion at the sight of each other. Willard was overwhelmed with the visual reminder of how much time slipped by and Kapp was struck by the prisoner’s grace in dealing with such a life-consuming sentence.

“I’ll do what I can to help you,” he reassured Willard, who’s now living with a nephew near Lake Merritt and visits Angela often.

On a late July night last year, possessing only $200 in cash—a parting gift from the state—Willard walked out of prison in Vacaville. All he had were the clothes on his back, a small bundle of books, photos and Angela’s letters.

He ambled past graffitied payphones with cut-off cords—relics from a life he’d once known. At 55 years old, and conditioned to only walk the span of a prison yard, he became exhausted from a simple trek to the Amtrak station. A woman let him use her cell phone, but his calls went unanswered. It was too late. No one expected his release until the next day and transitional housing wouldn’t open until the morning. So he waited, shivering in the park across the street.

“I looked up at the stars, at the big moon,” Willard says, “and I’d never seen that in so long after being in my cell every night for years. I just stared. I thought, ‘Hell, I’d rather feel this cold and sit in this park with all these homeless people than be looking at cement walls and gun towers.’ Just to hear the crickets and bugs that night in the park was music to me.”

Show us his real criminal history then I may buy your story. I do not want to hear it is confidential, show me convictions as an adult. Then I will give you an answer. Otherwise this is a SJ Inside worthless try to feel good article. Give us facts, not about some cut off cords. 3 strikers are felons, tells us more.

AND, I see this is not about a convicted 3 striker this is a love story about Raj Jayadev and his team of volunteers, all of who hate San Jose Police. Thanks! Can we move on. And we wonder why the SJPD is under 900 officers to serve a city of over one million.

I never see stories written about the victims of these felons. Why is that?

Speaking of victims, Kathleen, today commemorates the 20th anniversary of the OJ acquittal. (Raj would have fit right in with *that* jury)

The victims, Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman, were poorly served by our criminal justice system. But through shear anger, tenacity, and a desire to honor the memory of his son, Fred Goldman did the job that the State and the people of California had failed to do. For years Fred Goldman relentlessly hounded OJ into a state of desperation, finally backing him into such a financial corner that he committed a crime and then Mr. Goldman made sure that OJ was nailed. For good.

For Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman justice was finally served.

Progressives can get all joyful and weepy and rapturous all they want about Raj Jayadev and the criminals he is helping to put back among us. But if we’re talking true heroes of criminal justice, the person truly worthy of that status, for the epic, thoroughly committed battle he fought and won, is Fred Goldman. Congratulations Mr. Goldman. Well done!

Retired,

Show some compassion. Just because Mr. Birts chose to rack up felony strikes rather than raise and support his daughter when she was a child is no reason to doubt he is a man of fine character. And remember, according to the information being shared, he was only a burglar, you know, that otherwise decent class of lawbreakers who break in when they think no one is around and do as they damn well please with the property and privacy of good, hardworking Americans. And judging by the fine impression he’s made on so many — and you know those folks at the Innocence Project are upfront and objective, Mr. Birts’ life of crime was no doubt due to the circumstances of his struggle as a black man in racist America.

Please, don’t hold it against Mr. Birts because he came of age during a time when affirmative action was discriminating against whites in education and employment to make things easier for people like him. No matter how many advantages he was offered, or how many disadvantages were inflicted on white males to make room, the fact that Birts fell into a life of crime is all the evidence one needs to know that society just didn’t do enough for him. If you accept the notion that he took from society because society failed him, you can begin to see why his case attracted a “justice project.” Truth be told, I’m a bit surprised they haven’t demanded reparations for all the strikes society committed against him.

Whatever you do, don’t give in to bitter demands for “the truth” about his rap sheet, the financial and psychological toll his crimes took on his victims, the cost to taxpayers to raise his kids, prosecute, incarcerate, and now support him as a free man. Remember, the most useful fiction is the new truth, thus the truth is whatever the media says it is. This is a wonderful story. I think I’ll celebrate by buying a bigger gun. You should too.

http://www.callthecops.net/anti-police-protestors-victimized-street-gang-hilarity-ensues/#.U5sYDdeD-us.facebook

thanks Finfan but I have enough to protect my family from innocent 3 strikers

Another tear jerker about a serial felon. Thanks, Ms. Wadsworth. Let me wring out my handkerchief.

Kathleen: as you know well, criminals’ rights ALWAYS trump victims’ rights in California; and the press ignores the victims, too.

Was part of his sentence to pay restitution to his victims? Has he done so? If so, great. If not, why not?

Oh, and didn’t he find Jesus or convert to Islam when he was in the joint?

I look forward to an article about the Prop 36 felons who have been released who have failed. They are out there and their numbers will continue to grow. We can pat ourselves on the back with feel good stories about people who got their act in gear after a life of crime, but we stick our heads in the sand if we do not recognize that this choice has a real human cost that has and will be paid in order to free Willard Birts.

Hug those thugs, y’all!

> Hug those thugs, y’all!

Love it!

“Hugs for thugs”!

We may run out of water, and we may run out of taxpayers, but we are NEVER going to run out of social causes.

Wow. I would rather feel good about giving someone another chance who clearly has served enough time in prison and has made some positive changes to deserve it than feel grumpy and angry like you all. Don’t make your own happiness depend on someone else’s misery.

Then you’d be willing to rent him a room in your house, right NANCY27YL?