No sooner has Waldo Dave settled into the cafe’s corner table, his back to the windows that separate the indoor tables from the outdoor patio, when a loud thud! behind his left shoulder startles him. He whips around to see Waldo Steve’s face smooshed up against the glass. The two men—both in their early 60s, friends of more than 45 years—laugh as Waldo Steve peels his face away and heads inside, leaving behind a drizzly April morning and a contorted imprint.

He grabs a chair, sits down and pats an envelope that contains 167 pages of officially embossed U.S. Coast Guard records. “This was the ultimate goal,” he says of the highly anticipated mail, which arrived three weeks ago but took years of searching to obtain.

“This is what slams the door shut on everyone who says that our story is a bunch of bull,” Waldo Dave says.

As the story goes, in the fall of 1971, “five wise-cracking friends”—Steve, Dave, Mark, Larry and Jeff, who called themselves the Waldos after a wall they hung out on between classes at Marin County’s San Rafael High School—were given a hand-drawn map to a secret patch of cannabis in Point Reyes. The crop had been planted—and the map leading to it drawn—by a Coast Guard reservist named Gary Newman. Newman, brother-in-law of Bill McNulty, a friend of the Waldos who gave them the map, was said to have been paranoid about getting busted for planting the cannabis on federal property. The Waldos were determined to find the patch.

Week after week, they planned to meet at 4:20pm at a campus statue of Louis Pasteur. They’d get high, jump in Waldo Steve’s 1966 Chevy Impala, listen to its “killer” eight-track stereo and head to the Point Reyes coast in search of the treasure.

“It was always like cub scout field trips,” Waldo Steve says of the group’s safaris. “Except we were stoned.”

The Waldos never found the patch. But “420 Louis”—and later, simply “420”—became their secret code for pot. Today, the Waldos’ three-digit code has become mainstream universal slang for all things cannabis. Every year, April 20 (4/20), is the date of 420 festivals, 420 races, 420 Olympics, 420 college campus “smokeouts,” 420 publications, 420 beers, “420-friendly” real estate ads, California Senate Bill No. 420. The list goes on.

The Waldos, who describe their high school selves as intelligent, fit guys who were “seekers” rather than “stupid, slacker stoners,” live throughout Marin and Sonoma and work in fields ranging from financial services to independent filmmaking to the wine industry. Waldo Steve and Waldo Dave, the “talking heads” of the group, agreed to meet me prior to annual worldwide pot holiday to share their story. It’s a busy time of year for them.

“By the way, the Huffington Post just called,” Waldo Steve tells Waldo Dave as he flips through a heavy duty binder that contains hundreds of references to 420 culture in newspaper and magazine articles, from the New York Times, the L.A. Times, National Geographic, Time, Esquire and dozens more, records of dissertations on the sociological aspects of 420 and documented proof of conversations, handwritten eyewitness accounts, references to the marijuana map and copies of letters from the early ’70s—all supporting the Waldos’ claims that they were the very first people to use the term 420.

“Actually, we’re the centerfold in this one,” Waldo Dave jokes, pointing to a cover of Playboy.

The two men enthusiastically exchange inside jokes, noises, secret words, one-liners and impersonations. Their banter is a glimpse into the wild, adventurous world of the Waldos—intertwined with the beauty and the freewheeling counterculture of Marin in the ’70s. A golden era, they call it.

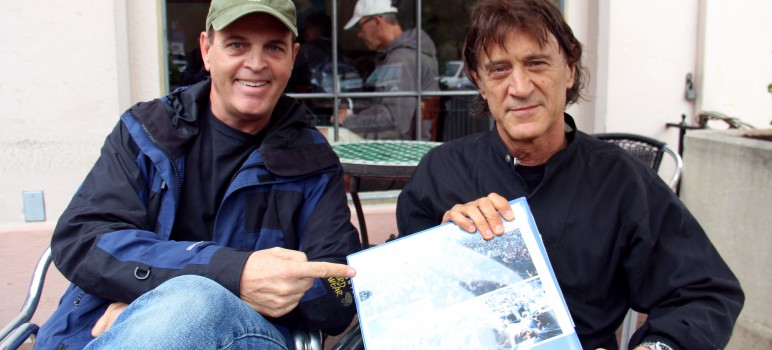

An old picture of The Waldos.

The Waldos don’t know what became of the map that revealed the Point Reyes cannabis patch. But “everything else” is preserved in a high-security bank safety deposit vault in San Francisco’s Financial District. One letter, written by Waldo Dave and sent to Waldo Steve after he had left Marin for college, read, My brother is Phil Lesh’s manager, and last weekend I had a job as a doorman backstage at a concert. I smoked out with David Crosby and Lesh … p.s. A little 420 enclosed for your weekend.

Another letter, from a friend who had also left Marin and was living in Israel, informs the Waldos that there’s “no 420 here.”

“It was an original little joke that turned into a worldwide phenomenon,” Waldo Dave says.

Cannabis culture

It’s 4:20pm in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, and puffs of smoke drift from groups of young people gathered on “Hippie Hill,” known among potheads as the place to light up. A drum circle provides a fast-paced, background beat, and an older guy dances, hands clapping above his head.

Next to a grove of Eucalyptus trees, three friends pass a joint around. When asked what 420 means to them, the one with long, dark dreadlocks proves that he’s adopted the Waldos’ secret code as his own. “Usually means it’s time to smoke,” he says with a crooked smile.

Do they know where the term comes from?

“If I can remember correctly, it was a group of high school kids who would meet at 4:20 to smoke,” says another. “My mom told me that.”

Dave recalls: “In about 1995 or so we started seeing ‘420’ carved into benches and spray painted on signs, and we said, ‘Hey, what’s happening here? This is starting to evolve. We’ve gotta start looking into this thing, you know?’”

Waldo Steve remembers Waldo Larry telling him that he was seeing more and more 420 paraphernalia— “more hats, more T-shirts, more everything.”

He said to himself: “I better get the story straight.”

A phone call to High Times magazine—“the definitive resource for all things marijuana”—resulted in the publication’s editor immediately flying to California to meet the Waldos and verify their claims. Following the original 1998 article in High Times, the origin story of 420 spread to other publications, one by one. “I think after the internet became big around 2000, then it started snowballing,” Waldo Dave says.

Ever since, the Waldos have fiercely defended their version of events, agreeing to meet journalists at their vault, get on camera and trek out to Point Reyes. Waldo Steve counts the number of times they’ve documented their story in the thousands.

“People keep trying to twist the story,” Waldo Steve says, noting the naysayers “come out of the woodwork” each year to attack and discredit the Waldos, or claim to have coined the term “420” themselves.

“There’s so many of ’em you can’t keep track of ’em,” Waldo Dave says. “It’s pretty hilarious. We’ve created a whole generation of 420-claimers now.”

“It’s such a fabled thing,” Waldo Steve adds. “People want to be part of a fable.”

“We’ve had people saying they thought our story was a fairytale,” says Waldo Dave, noting their recent search for the Point Reyes Coast Guardsman who gave them the map. “So we said, ‘Hey—we’ll go find this guy. We may not be able to find him, but we’re gonna try.’”

The missing link

The search for Gary Newman began six years ago. It was never easy. There were false starts, dead-ends, unanswered phone calls, unanswered letters and “no show” meetings in San Jose, where the Waldos had leads that the Coast Guardsman could be living.

“I was getting worried,” Waldo Steve says. “I was thinking, ‘God, this guy could die, and I’ll never get his side of the story.’”

More searching led to piles and piles of databases, and more dead-ends. Finally, the Waldos received a reply from Gary’s friend, Carol, who said that Gary most likely didn’t have a permanent residence.

“Somebody had to get into the streets,” Waldo Steve says. He hired private investigator Julie Jackson.

“He said he needed to find a guy that was basically homeless,” Jackson says. “It was like a needle in a haystack.”

Although she had little information to go on, Jackson was fascinated by the history of the Waldos. She informed the San Jose Police Department about what she was up to, in case she needed backup, and created a perimeter map of where Gary might be located. She also started reaching out to people who might know him.

“Usually I don’t take cases like that,” Jackson says. “But this one was too good to pass up.”

The phone call

Months after getting ahold of Gary’s friend but not hearing anything, Waldo Steve was traveling in a Texas “ghost town” near Big Bend National Park. “Big thunderstorms,” he says. “Cracks of lightning.”

He and his brother were the only people in a little emptied-out Mexican restaurant and saloon. “And between cracks of thunder,” Steve says, “I get a phone call.”

The woman on the line said, “This is Carol, I’m Gary’s caretaker.”

What seemed to be a hot trail led to months of more unreturned phone calls, unanswered letters and no-show meetings. And then, suddenly, everything changed. There was a date, a meeting spot and a time. And Gary showed up.

“Gary, we’ve been looking for you for so long!” Waldo Dave yelled when he first saw him.

Former U.S. Coast Guardsman Gary Newman (third from right) inspired the Waldos’ daily ‘420’ quests.

The Coast Guardsman who had played such a large role in the Waldos’ story, it turned out, was homeless and living on the streets of San Jose. They paid for Gary to stay in a San Jose hotel during the Super Bowl, in part so he could watch the game, and interviewed him to make sure that all records and accounts matched.

“Gary had no idea what he started,” Waldo Steve says. “I thought it’d be better for him to show us everything.”

He rounded up the Waldos, Gary, Carol, Jackson, Patrick McNulty (brother of the late Bill McNulty), and headed out to the Point Reyes Lighthouse, where Gary had been stationed. In a short video made by Waldo Dave, Gary talks passionately about his time there.

The official Coast Guard records the Waldos sent away for—and received three weeks before our interview—describe a decorated, life-saving Coast Guardsman. Finally meeting him after 45 years, the Waldos say, was like a reunion with a relative they never knew. And through the kindness and generosity of someone who Waldo Dave would only describe as “having a heart of gold,” Gary is no longer homeless.

“And now we’re like some big, happy family,” says Waldo Steve, who hopes that the official Coast Guard records and Newman’s own account will silence the 420 naysayers of the internet.

Waldo Dave seems less optimistic. “I don’t think it’ll be finished,” he says. “There’ll still be people saying, ‘Oh, that’s not true.’ But you know, they’re entitled to their own opinions; we have the facts.”

At some point, Waldo Steve says, he may take some of their documentation to a museum or auction house that offers forensics to get an approximate date of creation.

Or, Waldo Dave says, “I guess we could find that missing roach from 1971, underneath the seat.” He motions that he’s holding up a roach. “This is proof!”

This goes a long way to explain why pot heads look so vacant.

They’re vacant people.

“Let’s hang out and I’ll look at you smoking pot, and you look at me smoking pot.”

Groovy.

I’m trying to make February 23rd a special day, in honor of the .223 cartridge. I envision hundreds if not thousands of lawful rifle owners making a day of it locking and loading in San Francisco, provided of course, the city offers up the enforcement-free gathering spot and the $100k in city services it provides 420 burnouts.

Now THAT’S thinking outside the box.

Oh wow man, it’s like we found Robin Hoods split arrow and like Little John is still alive!

Snort, Snort, Puff, Puff, look at me I’m a Choo Choo Train!

False… And bad reporting…

The term “420” originated from a police code that was used to alert backup when pursuing suspects of public marijuana use. This code spread to university’s campus patrol.

Over time it became popularized.

Snopes.com has already busted that myth. There has never been police code for marijuana.

Maybe frustrated and outside the bubble should come inside with the normal people and instead of sounding like grumpy old men have some 420. All the negativity can actually get you no where interesting unless this is your life …negative comments,closed mind,afraid of the outside world hiding here.

Best Regards

I’m just saying

30 year 420 vet

Silicon Valley Executive 80k a year

**Peace ** Love **420

;-)

Mr. IMJUSTSAYING,

In 1971, while some in the Coast Guard and others in the military service were receiving “Purple Heart” medals in Vietnam, this supposedly “decorated” Gary, who is claiming to have been a Coast guardsman, was apparently being awarded the “Purpling Marijuana Leaf” undoubtedly for saving the life of a cannabis plant by adding more phosphorous to its potting soil.

While an assumed oversight, the reporter failed to point out the obvious comparison between Moses bringing back the stone tablets from Mount Sinai and “Gary the Stoner” bringing back a map showing a path to an illegal marijuana grow in Point Reyes. The reporter also missed an opportunity to glorify the fact that the “Amotivational Syndrome” associated with chronic use of marijuana may have been a factor in Gary’s becoming a “professional homeless”.

Along with the coining of the term “4/20”, (an apparently proud life achievement for this group of potheads), the reporter left out another phrase that merits recognition. The term “killer eight-track” was coined by a Highway Patrolman who was working the scene of a fatal head on traffic collision, on a coastal road near Point Reyes, that was caused by a group of would-be Rastafarians who would meet at a wall at their school, after doing their homework, of course, then, as the reporter writes “get high, jump in Waldo Steve’s 1966 Chevy Impala, listen to its “killer” eight-track stereo and head to the Point Reyes coast”.

At least if these latter day Cheech and Chongs are going to drive while stoned, they should at least have enough consideration to do it in the outer lane of a coastal road that has no guard rails.

> 30 year 420 vet

Silicon Valley Executive 80k a year

**Peace ** Love **420

Clear evidence of cognitive impairment.

Janitors make 80k a year in Silicon Valley.

“Executives’ make 8 million a year.

Oh, and . . . you forgot to say:

“Marijuana isn’t addictive. I can quit any time.”

IMJUSTSAYING,

Do you really think being a pothead qualifies you to set the standard for what’s normal? Given that 9 out of 10 Americans have not made smoking marijuana a regular part of their lives, your decision to do so, and continue to so so for three decades, makes you part of a very small minority? In addition, your delusion that smoking marijuana is necessary to live a happy life, and that people who think differently than you are closed-minded and fearful, suggests you have brain damage (smoke induced or not, I cannot know).

Your marijuana use may serve your psychological and/or medical needs, but please don’t fool yourself into thinking it serves your judgment, gives you insight into how others live, or in any way makes you interesting. Absent you posting something interesting, it appears you’re just a pothead.