Never mind respect for elders. The thousands of West Virginians who packed an arena on the last Saturday night in September were having a fine time laughing at California’s 85-year-old senator, Dianne Feinstein.

Egged on by President Trump—who mispronounced her name and used a doddering voice to impersonate her—the crowd howled as Trump mimicked Feinstein’s insistence that she did not leak the letter from a Palo Alto professor accusing Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanagh of sexual assault in high school.

“Uh, uh, uh, what?’’ Uh, no. Uh … no. I didn’t leak, the 72-year-old Trump stammered, further delighting the throng with a befuddled turn of his head to mock Feinstein’s conversation with her staff during Kavanaugh’s confirmation hearing. “Uh, one minute. Did we leak? Oh, no. We didn’t leak.’’

It’s too early to know how Feinstein, the ranking Democrat on the Judiciary Committee, will be remembered for her role in the Kavanaugh melodrama. But the attack from Trump, known to display a bully’s instinct for ridiculing his foes, underscored how the confirmation spotlight has brought questions about her longevity into sharper focus.

Is Feinstein—already the oldest member of the U.S. Senate—too old to serve another six years? Has her half-century in politics, more than half of which has been in Washington, made her more effective or out of touch? Do her moderation and temperate style put her at odds with her liberal constituents, or advance California’s agenda in the Senate?

Many progressive Californians are frustrated by Feinstein’s failure to aggressively advance their priorities, evidenced by the fact that in July the California Democratic Party’s executive board voted to endorse state Sen. Kevin De León, a development that perplexed the Washington establishment.

“Seniority means nothing if you don’t use that seniority to forcefully move policies that improve the human condition, in this case for all Californians,’’ De León said.

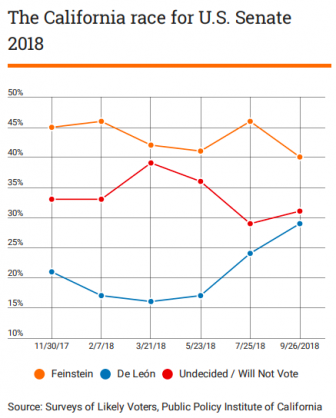

Feinstein, who holds a wide lead in the polls, insists she is a more productive senator than she was 26 years ago, bolstered by her rising influence and strengthened relationships with Democrats and Republicans.

As for President Trump?

“He’s a jerk,’’ she said in a recent interview.

As Feinstein makes a sixth bid for re-election, this much can be said with certainty: The very qualities that lead some in California to eye Feinstein as vulnerable—her political moderation, her non-confrontational temperament, and her age—are viewed by many in Washington as assets. And they have earned her a level of trust uncommon in the partisan body.

“I have great respect for Senator Feinstein. We’ve worked together on many topics,’’ GOP Sen. John Cornyn of Texas said in the midst of September’s ugly partisan debate over Kavanaugh’s confirmation.

“She’s very sincere,’’ piped in Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah). “I like her very much.”

Even Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina took time during his red-faced, finger-pointing rant against Democratic committee members to absolve her of leaking the accuser’s letter. “The one thing I know for sure is that Dianne Feinstein would not do this and did not do this,’’ Graham said, which didn’t stop him from calling for an investigation into how Democrats handled the matter.

Even Sen. Lindsey Graham of South Carolina took time during his red-faced, finger-pointing rant against Democratic committee members to absolve her of leaking the accuser’s letter. “The one thing I know for sure is that Dianne Feinstein would not do this and did not do this,’’ Graham said, which didn’t stop him from calling for an investigation into how Democrats handled the matter.

Comity, often fake, is common in the U.S. Senate. But Feinstein, a creature of protocol and etiquette, is widely regarded as a workhorse, not a show horse—the ultimate Senate compliment. Her relations with Republican colleagues are as close as any Senate Democrat.

“It goes back to my days as mayor,’’ Feinstein explained in a conversation in which she reflected on the horrific events of 1978 that led to her ascension.

********************************************************************************

Feinstein was in city hall the day Dan White murdered Mayor George Moscone. White, who had resigned from the Board of Supervisors two weeks earlier and then changed his mind, was enraged that Moscone would not rename him to the board.

Feinstein, not knowing what had just occurred down the corridor, tried to talk to White as he strode past her on the way to the office of Harvey Milk, San Francisco’s first openly gay supervisor and his perceived nemesis.

“Not now Dianne,’’ White said, before entering Milk’s office and shooting him at point-blank range. Feinstein was the first to see Milk sprawled on the floor, and as she reached down to check his pulse, her finger slid into a bullet hole.

“I was mayor because of assassination” she recalled from her Capitol Hill office, evoking the polarization and hate that followed. “I don’t tend to be a person who tries to pit one person against another. I find I get more done by working together.’’

Tall, stylishly dressed and with black hair revealing only a few streaks of gray, Feinstein is among the most recognizable figures in Washington.

She has sponsored or co-sponsored more than 500 bills, taken the lead to pass the nation’s most comprehensive assault rifle ban, successfully pushed a measure adding 1.6 million acres of California desert to the National Park system, and procured nearly half a billion dollars to restore Lake Tahoe. She was the first female chair of the Rules Committee and the Intelligence Committee, and the first woman ever on the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The question to many Californians is not her legacy, but whether Feinstein is still the most effective senator to represent an increasingly progressive and multicultural state, where at least 16 million constituents were not yet born when she first took office.

“We need more people who stand up for progressive values,’’ said Cliff Tasner, president of Americans for Democratic Action, Southern California. He cited her support for NSA surveillance, corporate bailouts, restrictions on union organizing, lengthy prison sentences, and her statement last year that Americans should have “patience’’ with President Trump—that she hoped he could change and grow into a “good president.”

Critics see Feinstein’s position as at odds with California, a result of spending too many years in Washington and with the moneyed interests who supported her.

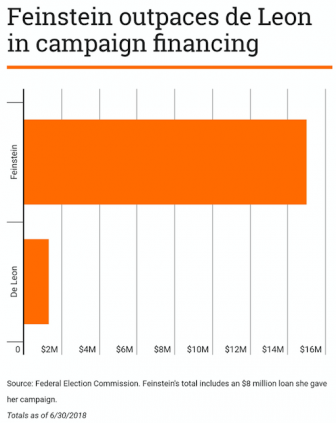

Since her first Senate campaign in 1992, she has far outraised most of her Senate colleagues, with sums more typical of incumbents running statewide in vast California with its pricey media markets: $4 million from lawyers and law firms, $2 million from real estate interests, $1.9 million from security and investment firms, $1.7 million from the entertainment industry, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

“Politician was never meant to be a job description,’’ said Bob Berry, Western Regional Director for U.S. Term Limits. “The longer someone serves, the more they are unplugged from their constituents.’’

“Politician was never meant to be a job description,’’ said Bob Berry, Western Regional Director for U.S. Term Limits. “The longer someone serves, the more they are unplugged from their constituents.’’

Yet the virtues of seniority—which determines placement on committees, speaking time in caucus meetings and office assignments—are widely admired in Washington’s corridors of power.

Barbara Boxer, who served alongside Feinstein for 24 years in the Senate, said it takes years to master the Senate’s arcane rules, appreciate the protocol, and earn the trust of those you need to get anything accomplished. And she described an “anyone but California” attitude that permeated the Senate and took years to overcome.

“When I left, I was a million times better than I was at the time I arrived,” Boxer said in a phone conversation from her Oakland waterfront apartment. “The fact is, the longer you are in the United States Senate the more power you have, the more you get done for your state, the more relevant you are to the country. Period.’’

She estimated Feinstein’s seniority and coveted spot on the Senate Appropriations Committee, which allocates federal funds, are worth “trillions’’ of dollars to the state.

Such measurements are impossible to quantify. Budget deals are cut deep behind closed doors, making it difficult to evaluate—let alone put a dollar value—on Feinstein’s influence. Not that her office doesn’t try.

********************************************************************************

This summer, Feinstein’s office boasted of procuring contracts worth more than $11 billion to build military aircrafts in the state; a $1.6 billion measure for an Expeditionary Sea Bay and two Navy fleet oilers in San Diego; and securing $30 million for seven C-130 air tankers to battle the state’s wildfires.

And Feinstein herself said federal transportation money to California had more than doubled in the past five years.

Barry, the term limit advocate, is unswayed: “Do we really want the kind of country where one state can plunder other states because it has a senior senator?”

Despite Feinstein’s moderate reputation, organizations that rank members across the political spectrum routinely place her to the left of about half her Democratic Senate colleagues.

The 2017 GovTrack ratings, for example, list Feinstein as the Senate’s 18th most liberal member, more liberal than Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts and more conservative than California’s junior Sen. Kamala Harris.

But that is not always in line with California, where some progressives see sheer calculation in her recent about-faces to now oppose capital punishment and support legal marijuana.

“She tends to be mealy-mouthed,’’ Tasner said. “We don’t have the time and luxury to be patient…. I don’t believe that moderation works.’’

Her support for robust intelligence gathering powers, such as a federal wireless surveillance program, has earned Feinstein the wrath of many civil libertarians. So they were surprised in 2014 when Feinstein—over the objection of the CIA and President Obama—released an executive summary report of a secret five-year investigation by her Intelligence Committee staff into waterboarding and other CIA practices most regard as torture. Her move shook the intelligence world; the CIA knew it was in trouble when it lost Feinstein.

********************************************************************************

On the campaign trail, De León and his supporters contrast his upbringing, raised by a single mother in the San Diego barrio of Logan Heights, with that of Feinstein, a physician’s daughter who grew up in a Presidio Terrace mansion in San Francisco. But behind the pretty pictures was private pain, as veteran California journalist Jerry Roberts chronicled in his biography “Dianne Feinstein: Never Let Them See You Cry.” The book’s opening sentence: “Dianne was still in grade school when her mother tried to drown her little sister in the bath.”

The stress of being the eldest child of an emotionally unstable mother and an exacting father instilled early in Feinstein a stoic strength that would serve her well on her fraught path to becoming San Francisco’s mayor. She made two unsuccessful attempts before Moscone’s 1978 assassination thrust her into the job—and even after that she withstood a recall attempt engineered by gun rights supporters.

Her straight-laced reputation dates back to her City Hall days, when closing gay bathhouses as a public health measure during the AIDS epidemic and vetoing domestic partner legislation may have been mainstream in much of America, but not in San Francisco.

To those who remember her as mayor, Feinstein’s longevity in the Senate may come as a surprise. Known to monitor police radios and sometimes show up at large blazes wearing a fireman’s hat, Feinstein was viewed as more comfortable in an executive role than as one of 100 senators.

The late political writer Susan Yoachum once described Feinstein’s mayoral style as “not so much hands-on as nails-dug-in.’’

So many were surprised when she decided to pass up the chance to run for governor in 1998, a seat she made no secret that she coveted. Feinstein had lost the 1990 governor’s race to Pete Wilson (it was the Senate seat he vacated that she was elected to) and it was assumed she intended to return to California.

Something changed after a term in the Senate. Feinstein enjoyed the national policy debates and the rarified air of the “world’s most deliberative body.’’ She hated campaigning, so the idea of six-year terms, with an opportunity to grapple with security and international issues, had great appeal. And despite a personal plea from President Clinton—who ironically called Feinstein from Air Force One while she and her husband, Richard Blum, were watching the movie “Air Force One”—she decided she could make her best contribution from the Senate.

Feinstein as mayor of San Francisco. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)

She has become a fixture on Sunday talk shows, the ultimate measure of Washington political renown. In June 2008, after Hillary Clinton conceded to Obama in their extended battle for the Democratic nomination for president, it was Feinstein who brought the two together for a reconciliation at her secluded Washington home, where she poured each a glass of Chardonnay and left them to talk.

When Barack Obama was inaugurated in 2009, it was Feinstein, as chair of the Senate Rules Committee, who served as the ceremony’s emcee.

The focus on her age, some contend, is sexist: Strom Thurmond served until he was Robert Byrd until he was 96. But those are exceptions. The average age in the current Senate is 61. Half of the U.S. Senate had yet to be born when Feinstein entered Stanford University. When she became a mayor, at least a dozen senators including Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and Cory Booker had yet to advance beyond 4th grade.

Some close to Feinstein say like many her age, she occasionally struggles to remember a name or word.

In a recent interview with the editorial board of the San Diego Union-Tribune, she was discussing the shabby treatment of some border-crossers, mistakenly referring to those seeking “amnesty.’’

“That’s the wrong word,’’ Feinstein said. “I’ve lost the word for it. It begins with an A.’’

“Asylum?’’ one of her interviewers asked.

“Asylum, thank you,’’ Feinstein said

But there are no signs her focus or clarity are waning. Never one to keep a busy political social life, she spends most of her time at her homes in Washington or San Francisco, or traveling the state, when she is not legislating.

Feinstein is often accompanied on both coasts by husband Richard Blum, a private equity financier, self-described “deal junkie” and former UC regent, whom she married in 1980. Over the years there have been suggestions that she is influenced by, and in a position to benefit, his various business interests domestically and overseas. Nonsense, she once told the New York Times: “We have built a firewall. That firewall has stood us in good stead.”

Her daughter from a previous marriage, Katherine, is a judge and former member of the California Medical Board. And Feinstein secured a spot on the 2016 Electoral College for her granddaughter, Eileen, who as a grade-schooler in the late 1990s helped write “Meet My Grandmother: She’s a U.S. Senator.’’ The book describes how her grandmother “Gagi” works out of an office on Capitol Hill, sometimes meets with the president, and unwinds by drawing flowers.

Many close to Feinstein can’t imagine her ever wanting to leave the Senate. Several said she has told them she feels—almost in a spiritual way—that this is her calling.

If re-elected, two years into her next term she would surpass Hiram Johnson as California’s longest serving senator.

Despite the jeers of West Virginians at a Trump rally, California consultant Rose Kapolczynski observed that Feinstein’s temperate tone is often an advantage—given that the pivotal votes would boil down to two moderate Republican women senators: Lisa Murkowski of Alaska and Susan Collins of Maine.

“Feinstein’s sense of history, her understanding of the process, her thoughtful approach, is the kind of approach that can bring a moderate over," she said. “There's a value in having someone who can talk to moderates."

As for Feinstein, she mentions that despite liberal criticism of her as San Francisco’s mayor, she left city hall with an 82 percent favorable rating. The complaints from today’s California progressives, she said, overlook the steadiness of her leadership.

“I have learned so much,’’ she said of her career. “And I’ve put that learning to use.’’

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics. Marc Sandalow is a CALmatters contributor and associate academic director at the University of California’s Washington Center. He is the former Washington Bureau Chief for the San Francisco Chronicle, and currently a political analyst for KCBS radio and Hearst Television. For more stories, polls and campaign finance information Election 2018, check out the CALmatters California Voter Guide.

Feinstein must resign.

I support the reelection of Senator Feinstein.

That way, when she is expelled from the Senate by the new Republican Senate super-majority, Republican governor John Cox can appoint her replacement.

Feinstein has been a political embarrassment of the Democratic party for many, many years. Me thinks all that “hair-coloring and facial make-up” has seeped into whatever brain she has left. Make that far-left.

The California Democratic Party is in complete disarray and fraught with relics usually associated with traveling Egyptian tomb robbers. Feinstein and Pelsoi are just two of the prominent animated stiffs from the ancient days of pharaoh that underscore the crying need for “term limits.”

Now, look who the California Democratic Party has allowed to rise in prominence.

State Sen. Kevin De León who has absolutely nothing to offer except his expertise on, “How to get elected and re-elected without doing a damn thing” would be a fitting compliment to Sen. Kamala Harris; a master of political buffoonery who is way out of her league. Combined, De León and Harris would continue to shame California to the world and drive the “conservative and middle-of-the-road Democrats” towards the “political-promised land-the Republican Party.”

David S. Wall

Where’d SJI get that pic of DiFi? Couldn’t they find a more recent one than from 1980?

Also, how did she amass her half billion dollar fortune? Selling votes and influence peddling must pay a lot better than it used to.

Between the lesser of two evils, I’m going with DiFi.