Yolanda Franco-Clausen avoids public restrooms. A local police officer with a slim build and a short haircut, she’d rather hold it until she gets home, or wait until her wife, Shay, can accompany her. Otherwise, because she reads masculine, strangers harass her in the women’s room, sometimes aggressively.

“It’s not a pleasant experience,” she says. Yolanda can fend for herself, but Shay’s presence—and her conscious, loud references to Yolanda as “girl”—prevent any trouble. Still, Yolanda says, “I would appreciate the opportunity to go to the restroom in peace.”

It’s the sort of thing you might expect in North Carolina or Texas, home to so-called “bathroom bills” meant to keep people like Yolanda, whose gender doesn’t fit neatly into a “male” or “female” box, out of public life. But even in a city where the pole at the county building flies every possible pride flag, Shay has to think about her partner’s safety.

“There’s not a day that goes by that I don’t remember that I’m a queer woman of color, getting up and walking out into the world,” she says.

“Even in San Jose. Even on my block.”

The Franco-Clausens have spent a lot of time walking blocks in Cambrian Park with their 12-year-old son, Josh, as Shay aims to become the first lesbian, the first Afro-Latina, and the first LGBT person of color elected to San Jose City Council in District 9’s June primary election. County Supervisor Ken Yeager, who has been an elected official in Santa Clara County since 1992, will term out at the end of the year, leaving a void in local LGBT representation that Shay Franco-Clausen hopes to fill.

On the state level, Evan Low, who was the first openly gay mayor of Campbell, represents the 28th district in the Assembly. Omar Torres, who is also gay, is running to keep his seat as vice president of the beleaguered Franklin-McKinley school board in San Jose. In Morgan Hill, openly gay Councilman Rene Spring won by a landslide back in 2016. But no out LGBTQ person has served on San Jose City Council since 2006, when Yeager left to join the county Board of Supervisors.

If Franco-Clausen loses, the San Jose council and county board will be without LGBTQ leadership for the first time in 17 years.

Rainbow Rising

Yeager smashed Santa Clara County’s lavender ceiling, becoming the first gay everything: elected official (in 1992, when he became a San Jose-Evergreen Community College District trustee), San Jose City Council member (District 6, in 2001), and county supervisor (District 4, in 2006). He raised the first rainbow flag at San Jose City Hall, spearheaded the creation of the county’s Office of LGBT Affairs, one of only a few such county offices nationwide, and pushed for an LGBTQ-focused homeless shelter, likely to open in San Jose before he leaves office.

In the ’80s, Yeager sought the first county funding for AIDS services, alongside lesbian activist Wiggsy Sivertsen, then led the push for the county’s “Getting to Zero” program, which aims for zero new HIV infections and AIDS deaths.

“Nobody anywhere in this country has been responsible for more political progress for the LGBTQ community than Ken,” says Dave Cortese, who was elected to the San Jose City Council the same year as Yeager and later joined him on the county Board of Supervisors in 2008.

But Yeager will leave office at a critical time for his community. Nationally, LGBT rights that might have seemed secure before the 2016 election are in peril: U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ Department of Justice supported groups that would discriminate against LGBT people in the name of religious freedom and removed trans people from the law that’s supposed to protect against sex discrimination. The president tried to prevent trans people from joining the military, though that has mostly failed. The Texas Supreme Court ruled against same-sex marriage benefits, ignoring the federal Supreme Court ruling from 2015 that allowed them everywhere.

Republicans in Georgia passed a state Senate bill to prevent same-sex parents from adopting, and the Kansas Republican Party voted against “all efforts to validate transgender identity” in February. And violence against LGBT people is way up in the last year, with an 86 percent increase in homicides. Just in the first two months of 2018, an attacker shot blindly into the only trans bar in Las Vegas, a neo-Nazi killed a gay college student in Orange County, and seven trans women were murdered.

Public support for LGBT people declined in 2017 for the first time in years, according to a GLAAD annual study.

It’s enough to make local LGBT people worry, despite a phalanx of strong California laws that protect housing, employment, marriage and adoption rights. The housing crisis hits LGBTQ people especially hard.

“Housing is a significant issue in this area, and if you look at Santa Clara County, 40 percent of homeless youth are LGBTQ,” says Paul Escobar, vice president of the Bay Area Municipal Elections Committee (BAYMEC), the South Bay and Central Coast’s only LGBTQ lobbying organization. In a rental market as tight as this one, when landlords have their pick of renters, it can be tough to tell whether a rejected apartment application was a case of discrimination.

Mental and physical health challenges remain, as well.

“Suicide rates are still too high,” says Yeager.

Santa Clara County runs a health clinic for homeless transgender people, but except for those with Kaiser insurance, anyone who’s not homeless has to go to Fremont to access hormones. “Lots of physicians still don’t know how to treat LGBT people or even have the conversation about their health needs,” Yeager says.

None of the candidates vying for Yeager’s seat identify as LGBT, leaving his legacy in the hands of straight politicians. “The race to elect someone new in that position is of particular interest to us,” says Escobar.

BAYMEC issued a dual endorsement for his replacement: San Jose Unified trustee Susan Ellenberg and San Jose Councilman Don Rocha.

Back in 1979, religious groups backed ballot measures to block anti-discrimination laws from passing, knowing voters didn’t really want to support gay people.

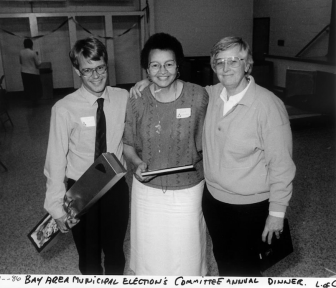

Ken Yeager, former San Jose Councilwoman Iola Williams and San Jose State professor Wiggsy Siversten (left to right) at the inaugural gala for the Bay Area Municipal Elections Committee, the LGBTQ civil rights advocacy group they co-founded in 1986.

They were right: 70 percent of San Jose voters and 65 percent of county voters opposed the ordinances. In contrast to San Francisco, where mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk passed an anti-discrimination ordinance in 1978, the ballot measures reminded gay South Bay residents that their neighbors didn’t want them here. Of course, San Francisco wasn’t a haven, either. Milk and Moscone became widely hailed as gay rights martyrs later that year, when disgruntled former Supervisor Dan White—the only one on the board to oppose the gay rights ordinance—shot and killed them in San Francisco City Hall a half-hour before officials planned to announce his replacement.

But explicitly anti-gay politics tend not to go over well in San Jose anymore. Former Mayor Chuck Reed opposed gay marriage, leading Yeager to avoid meetings with him as recently as 2013. In 2016, Sergio Jimenez beat out Steve Brown for the District 2 council seat after Brown, who’d been endorsed by Councilman Johnny Khamis, current District 7 council candidate Van Le, and the county Republican Party interrupted a news conference to state his support for business owners who refuse to serve LGBTQ people under the guise of “religious freedom.”

Still, you can count the number of LGBTQ candidates who’ve run for San Jose City Council on one hand: Yeager, the late Paul Wysocki, who lost the District 3 council seat to David Pandori in the ‘90s, Steve Kline who lost the District 6 seat to incumbent Pierluigi Oliverio in 2012, Tim Orozco who lost the District 4 seat in 2015 to Manh Nguyen—and now Franco-Clausen.

That might have something to do with how San Jose government is wired.

“Unlike a lot of smaller cities like Palm Springs and West Hollywood, running for a City Council seat here in San Jose is almost like running for mayor of a midsize city,” Yeager says. In a jurisdiction of a million-plus people with only 10 council seats, each candidate competes to represent about 100,000 residents. In such a big race, Yeager says, “You’ve got to know what you’re talking about, you have to have a whole army of volunteers, and you have to raise a whole lot of money.” All of that can be harder to come by when you also face stigma for one or several parts of your identity.

Franco-Clausen has mostly found that her District 9 neighbors have been curious about her. “People will say, ‘Oh, are you the lesbian?’” she laughs. “They want to talk about it. They want to be better informed.”

One of 11 siblings raised on Rudy Drive off Blossom Hill Road, Franco-Clausen has known she was gay since she was a girl. “I was in love with Amanda with the red hair,” she says. But she didn’t come out until well into adulthood, after giving birth to three kids. “I said, I want to give, but I can’t if I’m living this internal lie. So I took my chances and I came out to the world.”

She lost friends and family—“the people who I thought wouldn’t support me, supported me, and the people I thought would support me didn’t support me”—and met Yolanda within a year, when they were students at Cal State-Long Beach. They recognized each other at a coffee machine outside the computer lab where Shay was writing a paper. “She’s like, ‘Do you like coffee?’ and I said, ‘I loooove coffee,’ and that was it,” Shay says. “We sat and talked, and she was telling me something intense. I grabbed her hand, and we have been together since that moment.”

In addition to raising Shay’s three kids—a student at Willow Glen middle school, a student at Menlo College, and a tradesman in Los Angeles—they took in two foster kids who were phasing out of a group home and San Jose Job Corps.

San Jose might not look like the Castro, but gay families like the Franco-Clausens have quietly populated their suburban-feeling district for years.

“There’s lots of gaybies,” says Shannon Casey, a consultant for Franco-Clausen’s campaign and VP of the South Bay Stonewall Democrats. “There’s hundreds of families in the South Bay who will be very excited to have somebody who looks like them in office.”

Franco-Clausen was tickled to meet an older gay couple on the street she grew up on. They remembered her as a baby and threw her a fundraiser.

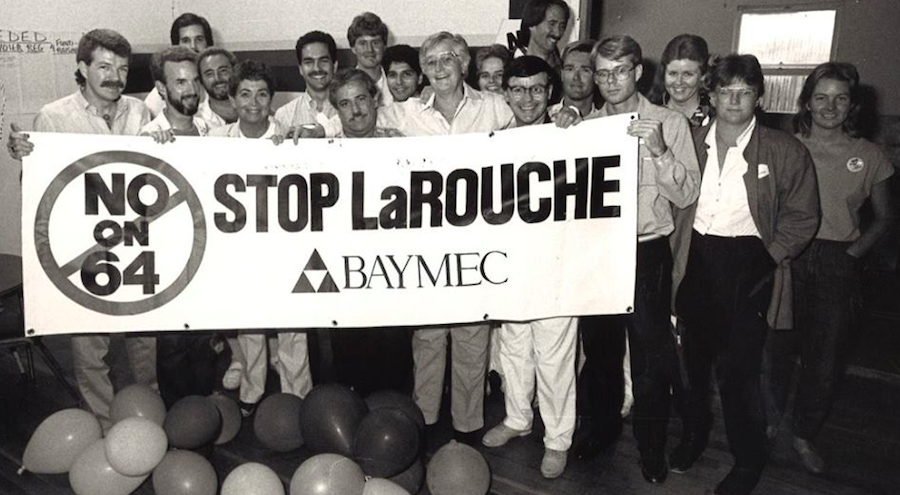

South Bay activists protest an initiative by political gadfly and cult leader Lyndon LaRouche that sought to quarantine AIDS patients and anyone diagnosed with HIV.

A Second Shot

Twenty-four years ago, doctors told Raymond Mueller to quit his job and buy a funeral plot. Mueller, who’d tested positive for HIV in 1986, took their advice.

“I had a plot on a payment plan,” he says.

Like many gay men of his generation, he became an activist after his diagnosis, fighting stigma-fueled government sluggishness that led to hundreds of thousands of deaths. When Lake County, Illinois, held its first World AIDS Day event, there were two speakers: Mueller and the coroner.

After more than a decade of protest, scientific breakthroughs finally led to better drugs, and Mueller and his partner could think about the future.

“It was pretty obvious I was no longer dying,” Mueller says, and they hoped to adopt a child in their new hometown of San Jose.

The adoption agency called the day after the Silicon Valley Pride march, as Mueller was wrapping up loose ends on the pride board, and he enrolled their new 6-year-old son at Russo Academy in the Alum Rock Union Elementary School District a week later.

Now he’s running for school board in that same district, as the parent of a seventh-grader who calls Mueller “Papa” and his partner “Daddy.”

Mueller joined the independent Citizens Oversight Committee for the Alum Rock school district as a parent representative, overseeing how the district spends hundreds of millions of construction bonds.

Alum Rock Union school district candidate Raymond Mueller is running in hopes of reforming a dysfunctional board. He’s one of only a handful of LGBTQ candidates in the South Bay.

The district is grappling with a state audit, a financial takeover by the Santa Clara County Board of Education, and a district attorney investigation. The district re-hired the scandal-prone Del Terra Group to manage its bond money, despite a fraud investigation that found that the district paid the attorneys when they weren’t providing services.

And in August last year, the board replaced Twitter-happy President Khanh Tran with his buddy Esau Ruiz Herrera on a night when Tran’s expected successor, the reform-minded Andres Quintero, was not at the board meeting, in a move that angry parents called “scripted.”

Parental frustration boiled over in early March, when about 400 students and staff walked out of Alum Rock schools in protest of their “unscrupulous abuses,” according to East Side nonprofit SOMOS Mayfair.

Mueller was among them. He’s running as a reformer against three incumbents this November in an election that the top three vote-getters will win.

“I have not been taking my child to these meetings because that’s not the representative concept I’d like him to take home and say, ‘Oh, well, that’s how we can act,’” he says.

He’s frustrated with the “cronyism, the infighting, the bickering, the immaturity,” and wants to use bond money to fix old school buildings, not just build sexy, vote-getting new ones. Last summer when temperatures spiked, he says, “children were actually in Alum Rock schools without air conditioning,” since the AC was broken, “and you couldn’t send them outside, since it was 108 degrees.”

The question is whether he can win. Mueller is well aware that his neighborhood voted for Proposition 8 and against gay marriage a decade ago, but he feels comfortable in the ethnically diverse, working-glass East Side.

“Nobody’s ever egged our house,” he says. “We live authentically there.”

At the same time, he’s realistic.

“There will be be people who support me to my face and then they go to the ballot box and they’ll support a different person,” he says. “But I think I’ve got a shot.”

Quiet Bias

No one seems to agree: Will quiet bias in the voting booth keep Yeager’s successors out of office this year, or has a shifting statewide consciousness made the South Bay a safe place to run a gay campaign? Mueller isn’t sure.

“My postcards won’t be rainbow,” he says.

Jeffrey Cardenas, president of the South Bay chapter of the Stonewall Democratic Club, is more optimistic. “We have some of the most educated voters in the country in our county” on LGBT issues, he says.

Yeager’s time in office has had a clear impact on the rest of the board. “Many years ago, I got my LGBTQ values right,” says Cortese. “But I learned how to put them into action with courage and resolve by watching Ken.” Cortese has long since apologized for sending out a homophobic mailer when he ran against Yeager for a state Assembly seat in 1996, an election they both lost to Mike Honda, and the two became allies as supervisors.

In San Jose’s District 9 race, Franco-Clausen, a former board member of BAYMEC, has already won the organization’s endorsement. But her straight opponents believe they can serve San Jose’s LGBT voters just as well.

If elected, Shay Franco-Clausen would be the first Afro-Latina lesbian on the San Jose City Council.

“Obviously—or maybe not obviously—I don’t identify as LGBTQ,” says Kalen Gallagher, a member of the Campbell Union school board. “But since college, I’ve done my best to stand up for what’s right.” He cites resolutions for marriage equality and funding for the LGBT student center at UC Davis when he was in student government there, in addition to requiring gender-neutral bathrooms in Campbell high schools, as evidence.

San Jose Unified trustee Pam Foley, the leading fundraiser in the District 9 race as of January, emphasized her personal connection to the community; her brother, Tim, died of AIDS in 1996.

“My daughter carries his name in honor of him, as her middle name,” Foley says. San Jose Unified also created gender-neutral bathrooms in its high schools during her tenure.

“I try to use the correct pronouns,” she says.

Foley was unsure about what the LGBTQ community might need from a council member. “We have marriage. We have protection in so many areas, so I don’t actually have a sense of what might be out there that is an issue,” she says. District 9 candidates Sabuhi Siddique and Rosie Zepeda declined to comment.

Franco-Clausen argues that empathy is no substitute for lived experience. “When you have an LGBT person on there, there’s no questions,” she says. “When it comes down to crunch time, are you going to put your neck out there and say I endorse this because it’s important?” With straight politicians, she says, “We have to wait and hope they do.”

Escobar maintains that the community needs both. “If you look at the gay rights movement historically, we couldn’t have gotten where we are without strong straight allies too,” he says. “But representation is key.”

The Next Generation

Beyond Franco-Clausen, Mueller, and Torres of the Franklin-McKinley school board, the pipeline for LGBTQ candidates in the South Bay is less than robust. In a strongly Democratic county, the Stonewall Democratic Club is small.

“We could definitely have more attendance,” Casey says.

There are no trans members of the club, Cardenas notes.

In fact, California’s first trans congressional candidate, Terra Snover, lives in Mountain View, but she ran for office in Stanislaus County against Jeff Denham in November, dropping out before the election. She did so without support from the South Bay LGBTQ establishment; no one interviewed for this story mentioned her.

“The people in office are predominantly cis white gay men,” Casey says. Though of Torres and Yeager, the two current LGBTQ politicians in office in Santa Clara County, only Yeager fits that profile.

But the future is non-binary. A UCLA study found that 27 percent of California teenagers are gender nonconforming. Trans and gender nonconforming people are just starting to break through within South Bay politics; out of the 14 members of BAYMEC’s board, traditionally a steppingstone for public office, only one uses they/them pronouns.

Cardenas pinpointed the problem his own club is grappling with.

“The struggle that underserved communities face is because we’re not visible enough, therefore we don’t have a pipeline,” he says. “But we don’t have a pipeline, so how can we have people who are more visible?”

More Tribalism.

How about you run because you think you are the best candidate?

I completely agree. I don’t make my voting decisions on someones sexual orientation. Actually, I’m a bit turned off. All I read about is she is gay. I don’t care.

I don’t even care if she takes her wife to the bathroom. Can she do the job?

What is sad is that there are several Santa Clara Council members trying their best to block a member of the LBGTQ community from the Planning Commission.

Because they are a member of the LBGTQ community or because they disagree with their idea of what the Planning Commission will do?

What would be sad is if we looked past bad ideas or nonworkable plans just because the person who held them was from the LBGTQ community.

Tribalism – is a problem that the Bay Area is in denial over.

> several Santa Clara Council members trying their best to block a member of the LBGTQ community from the Planning Commission.

LBGTQ was the person’s relevant qualification?

Not the way an intelligent person would pick a surgeon, an airline pilot, a pastor or a Planning Commission member.

> Still, you can count the number of LGBTQ candidates who’ve run for San Jose City Council on one hand:

No. You can’t.

There very likely have been “gay” candidates who did not flaunt their “gayness” and therefore cannot be counted.

Percent of Americans who identify as LGBTQ: 3.8%

Percent of Media Coverage of Americans who identify as LGBTQ: Seems like 90%

For everything else, there’s MasterCard.

I understand these comments to a degree, but wonder if people would have said the same thing if we were talking about a black, Asian or hispanic politicians and political candidates. I also believe that younger people have a feeling that this (being an LGBTQ candidate) is no big deal so why talk about it? If you had lived through times when there was much more discrimination against LGBTQ people perhaps you would understand better. I agree about the best person for the job of course, but at the same time diversity is important because it brings with it a lifetime a perspective from a certain vantage point.

> but at the same time diversity is important because it brings with it a lifetime a perspective from a certain vantage point.

What the hell does this mean?

This is not a serious argument. This is just political conditioning.

Brandonm, yes I would make the same arguments if the candidates were black, Latino, Asian or white. Anyone who sells their candidacy on their tribal affiliation misses the point of the republic. We trust in representative democracy because we choose leaders who we think will do well for all citizens, not just their tribe, so sell yourself on what you can do for everyone. If your contention is that only lived experience can inform good leadership, why would anyone white or straight vote for anyone black or LGBTQ? And diversity is not an argument, because there is significant diversity within each tribe, more so than between them. If not, the whole multi-ethnic, multi-cultural argument is blown out of the water. This is, of course, different to protesting laws and public institutions that discriminate against their or any tribe. The government should never discriminate against any group, that would be an assault on the idea of America, even if that group is the majority. We have fought civil wars against this and passed amendments to further manifest the idea of equal protection under the law.

You may vote for the person you believe will best represent everyone. However, most people vote for the person that will represent their particular point of view, often on only one issue. That’s one reason why we have so many one trick ponies in local government.

Does Pierre Luigi count?

https://youtu.be/3AaJcIG__rc

No, Pierluigi fits this category.

“A UCLA study found that 27 percent of California teenagers are gender nonconforming.” Yeah, right.

The wages of SIN is still death. You flaunt your sexual preferences in our face and damn us when we dont share your view. I dont want to know what my city council representative sleeps with. I want to know you are going to get roads paved, spend my tax dollars wisely, keep your nose clean, stay out of trouble and scandals and make San Jose a little better than the way you found it. Homosexuality is wicked and immoral. THATS JUST THE FACTS. If you do a good job and treat the office with respect I will vote based on believing you…..not because you are immoral or a pervert.

Guess this article forgot about the openly gay candidate for Santa Clara city council in 2016, Anthony Becker, he is currently up for Santa Clara planning commission and there were rumors circulating he will run in 2018 again for city council yet it is said that depends on the planning commission result

> “Why a Bar Can Boot Trump Supporters, But a Bakery Cannot Deny Gay Customers”

http://www.thedailybell.com/news-analysis/why-a-bar-can-boot-trump-supporters-but-a-bakery-cannot-deny-gay-customers/

So, can a bakery in Silicon Valley refuse to bake a wedding cake for a gay customer wearing a Trump hat?

You actually make it appear really easy with your presentation but I in finding this topic to be actually something that I believe I’d by no means understand. It seems too complicated and very broad for me. I’m looking forward on your subsequent publish, I’ll try to get the dangle of it!