Stacey McGruder, clad in a tan summer dress and matching flats, feels uneasy walking into the visitors’ lobby of Elmwood Correctional Facility.

“This is weird,” she whispers, passing through the double-door west gate entrance of the jail, the larger of two facilities in Santa Clara County with more than 3,000 inmates. “I feel like I shouldn’t be here, at least not on this side.”

Last time McGruder set foot in Elmwood, she had to change into a baggy green-and-gold jumpsuit, a repeat offender and state prison ex-con locked up again in 2009 on a DUI charge and probation violation for previous convictions that included assault with a deadly weapon. As an addict in and out of the system for 17 years, she accepted her incarceration as inevitable.

Her second and last stay at Elmwood ate up 18 months of her life. It was here she earned a new name, Steeda, which over the years turned into an acrocnym: Striving To Embrace Emotional Damage Acquired.

“I wasn’t a good person here at first,” says McGruder, now 30 years old, about three years clean and employed as a mentor-peer counselor by the very probation department that kept an eye on her after her most recent release on Valentine’s Day 2011. “I didn’t accept responsibility for myself. I was rolled up [sent to solitary]. I’d give the guards a bad time. I didn’t want anything to do with anyone.”

That changed toward the end of her spell. Earning a new name meant her peers trusted her, she says. She chose to reinvent herself, an effort that actualized over the course of thousands of words read in a self-help book and thousands more penned on paper, in letters to and from her adopted mother, her best friend, her grandma, her birth mom, her three sisters, a local church and her two daughters. Steeda would wake up, sit at her desk, read, write and envision putting together a support group once she got out. She gladly treated the routine like work.

“I wonder if the COs [correctional officers] will recognize me,” she says now, glancing around, fidgeting with the strap on her shoulder bag. “They’ll be like, ‘Her? What the hell is she doing here?’”

This day, a sweltering June afternoon, McGruder visits as a community organizer looking for some answers. The sheriff’s office recently proposed limiting all mail sent to inmates to postcards instead of the envelope-enclosed letters currently allowed. Sorting through the 200,000 letters a year is tedious, jail officials say. Some of the letters are soaked, spliced or stamped with drugs: PCP, acid, meth and other contraband. Some contain needles. Some hide gang communications. The idea of switching to simply postcards—outside of inmates’ communications with their attorneys—would save money and time.

“We have to think about the safety of our employees, but also of the inmates,” says Deputy Kurtis Stenderup, spokesman for the sheriff’s office. “It’s for the greater good.”

McGruder and others aren’t buying the safety line. “It’s about money,” she says. “But whatever money you save, it’s not worth the cost to the people inside.”

Nationwide, dozens of county jails have adopted postcard-only incoming mail policies after Arizona’s Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio started the trend in 2007. Each year, more jails adopt similar mail policies—and virtually every time there’s a public backlash and legal challenge.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has won cases in Colorado and Florida, and in April a federal judge in Oregon set a precedent when he ruled that limiting mail to just postcards is unconstitutional and violates First Amendment rights. But the ruling holds no sway in California.

Inmate advocacy group Prison Policy Initiative authored a report about postcard-only policies in February that lambasted the practice for placing a disproportionate burden on black and low-income families. Visiting hours are already limited and phone calls can cost about $25 for 15 minutes. Postcards also cost about 34 times more per word than paper and envelopes.

John Hirokawa, head of Elmwood and the main jail complex in San Jose, proposed the local policy this spring, citing safety concerns and the interest of saving time and money. When inmates got wind of it, they wrote home.

Families started talking, worried they’d lose connection with loved ones behind bars. No more report cards, bill receipts or medical information would get mailed back and forth, unless through an attorney. The change in policy, they argued, would be disproportionate to the threats—only 10 percent or less of senders even try to smuggle anything, but everyone would be punished.

ACLU attorney Michael Risher sent a letter in May to Hirokawa urging him to drop the idea, arguing that it’s a First Amendment violation. Plus, California law specifically prohibits limiting inmates’ mail.

“A postcard is not a letter, and restricting correspondence to a small card rather than multiple sheets of paper that can comprise a letter is certainly a limitation on the volume of mail that can be sent or received,” Risher says.

McGruder, with help from nonprofit community group Silicon Valley DeBug, called for a public meeting in early June. Hundreds of people showed, many of whom tearfully shared the pivotal role longform correspondence plays in changing the lives of both inmates and their families.

McGruder and the probation support group she leads, Sisters That Been There, write to inmates every week, sending notes of encouragement, magazine clippings and pictures. The women who write back—some have no contact with anyone on the outside—say the letters give them hope.

Hirokawa deferred a decision until he got more community feedback, and he won’t decide on anything until at least one more meeting, he says. That probably won’t take place until September, which buys McGruder time to rally more opposition. If the county enacts the policy, it would be the fifth in California and the only one in the Bay Area.

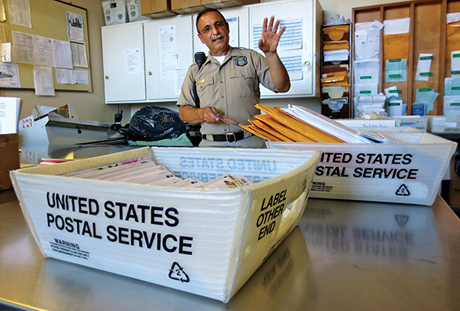

The mailroom at Elmwood receives the bulk of the county’s jail correspondence. It’s a small room with a vaulted ceiling and aluminum-plated counters for sorting. An inmate sits to one side to observe the process, to keep the jail employees accountable, Deputy Stenderup explains.

Mail sorters wear latex gloves when handling letters. McGruder asks Custody Support Assistant Salvatore Lombardo if he ever feels unsafe. He says no. So, it’s more a time issue? Yes, he answers.

It takes two-and-a-half full-time workers to rifle through all the mail. The custody support assistants earn between $37,109 and $49,668 a year. If they weren’t sorting mail, they’d spend more time “in different types of programs,” Hirokawa says. This includes managing the property room, answering grievances, and managing cleaning crews, facility maintenance and the laundry.

Hirokawa says he’s open to suggestions and will consider those that were offered at the June community meeting. “There were some viable solutions,” he says, “but each one comes with its own challenges.” While changing the jail’s mail policy doesn’t require approval from the county Board of Supervisors, the board could delay or stop any move it opposes. Supervisor Joe Simitian has asked for Hirokawa to report to the board about the plan.

In the mailroom, about one-thirtieth of the correspondence gets rejected—two foot-high stacks in the past month. Each letter sent back requires a form filled out and reason stated. If there’s contraband, a criminal case is opened, which goes to the District Attorney’s Office.

“It’s incredibly time-consuming,” Stenderup says.

To McGruder and many others, though, it’s not wasted time.

“Every big facility is going to need some sort of mail organization,” she says. “It’s OK if that’s someone’s job. It’s OK to pay someone to do that. If [the jail] is trying to save money, that’s not an area that should be cut.”

I’m so worried about those poor inmates. Jail just isn’t going to be as much fun as it ought to be.

Here is some free advise! Don’t commit crimes and you won’t have to go to jail! It’s actually real easy to do.

—only 10 percent or less of senders even try to smuggle anything, but everyone would be punished.

Ten percent is an incredibly high number. 100 out of every thousand.

In the mailroom, about one-thirtieth of the correspondence gets rejected—two foot-high stacks in the past month. —two foot-high stacks in the past month.

So is it ten percent or 7.7 percent? A stack of mail 2 feet high got rejected in the past month? If it’s 1/13 of the total, then they got a stack of mail 26 feet tall this past month. That’s a lot of mail.

Each letter sent back requires a form filled out and reason stated.

That has to be at least a foot high stack of forms that get filled out every month. Maybe multiple feet if the forms have copies.

—two foot-high stacks in the past month.

A stack of mail 2 feet high is rejected?

phone calls can cost about $25 for 15 minutes

$1.67 per minute? Really? Why?

Postcards also cost about 34 times more per word than paper and envelopes.

This is in the category of a very small number multiplied by a very large number still being a very small number. If someone can come up a real world instance where the contents of one envelope filled up even 10 postcards, I’d love to see it.

McGruder and others aren’t buying the safety line. “It’s about money,” she says. “But whatever money you save, it’s not worth the cost to the people inside.”

It is about the money. It’s not a cost to the people inside, it’s about the cost to the taxpayers. It’s not a civil rights issue. It’s a convenience issue. Why is it that convenience issues that relate to regular folks, like the number of clerks at the DMV, get the short shrift, while everyone worries about inmates getting the short shrift?

The other issue that isn’t being addressed is how efficient are the “mail sorters”? If they fail to find even 1% of the illegal mail, what threat does this present to the people that have to work in the jail. If going to postcards brings this down, I’m all for it.

send love, hate mail but leave your illegal drugs, etc. at Home. Seems things run the same for families in or out of jail.