One morning at the end of August, with the capstone of his political career in the balance, state Sen. Kevin De León retreated to his Capitol office and turned on the TV. On the screen, colleagues who had known the Los Angeles Democrat for years debated his landmark bill to eliminate fossil fuels from California’s electrical system. The bill was big, attracting national attention. But it wasn’t going to pass, at least not on this vote, and no smart politician sets himself up for a public loss.

So here he was, hunkered down in his half-emptied workspace, when talk of the bill’s merits morphed into a debate about De León himself.

“Tumbleweeds,” Assemblyman Adam Gray of Merced had just fumed, resurrecting a gaffe De León made in 2014 when he used that word to describe the Central Valley and inadvertently insulted the entire region.

“That is the disrespect and disregard this institution shows to those of us in rural communities,” continued Gray, a conservative Democrat. He cast the clean electricity bill as De León’s latest insult, saying it would make life more expensive for rural Californians just so the Angeleno could pander to progressive voters.

“You don’t have to like the author,” pleaded Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez Fletcher of San Diego. She quickly added that she considers him “a great guy,” but the room erupted with knowing laughter.

Upstairs in his office, De León didn’t flinch. He sat with his legs crossed, chin resting on a hand, dark eyes trained on the TV as voting began. The bill fell four ayes short of passing, but that temporary setback—it ultimately would become law—resonated less than Gonzalez Fletcher’s revealing admission.

Her acknowledgement encapsulated both the complexity of his legislative career and the factious nature of his campaign to unseat U.S. Sen. Dianne Feinstein. Few politicians can match De León’s hard work, persistence and political instincts, yet few spend as much time dealing with people, even some political allies, who personally dislike them. The 51-year-old, who remains lean and tall, barely gray at the temples, characterizes it as the price of success.

“I’m willing to fight for what I believe in,” De León told me, “and willing to fight for what’s right.”

After 12 years in the Legislature, De León—the first Latino in modern history to lead the state Senate—is now forced out by term limits. He leaves a stack of accomplishments born of his penchant for aggressive politicking and his embrace of controversial legislation. Laws written by De León advance progressive priorities—combating climate change, helping workers save for retirement and protecting undocumented immigrants.

But he’s also developed a reputation for power tripping and chasing the spotlight. He feuded with Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom over credit for gun-control legislation, an issue De León has long championed. He highlighted his fight against the Trump administration by spending taxpayer money to hire Barack Obama’s attorney general.

And, though never accused of wrongdoing, De León has been near the center of the Capitol’s most serious ethical crises. He was a witness in the federal corruption case that sent one senator to prison, and was housemates with another who resigned this year under investigation for sexual harassment.

“He’s not everything he says he is,” said Dana Williamson, who worked closely with De León when she was a top aide to Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown. “He’s created this narrative that he’s this progressive champion, and he always does the right thing, and I just don’t think it’s right.”

Perhaps nothing De León has done is more polarizing than his challenge to Feinstein, a 26-year incumbent and Democratic legend. He is attacking her from the left, energizing progressives by framing himself as a more forceful resistance against President Trump. Yet with 32 U.S. Senate candidates on the ballot in the primary, Feinstein not only trounced De León statewide, she defeated him in his very own district. Then he scored a huge coup, convincing leaders of the California Democratic Party to endorse him.

Perhaps nothing De León has done is more polarizing than his challenge to Feinstein, a 26-year incumbent and Democratic legend. He is attacking her from the left, energizing progressives by framing himself as a more forceful resistance against President Trump. Yet with 32 U.S. Senate candidates on the ballot in the primary, Feinstein not only trounced De León statewide, she defeated him in his very own district. Then he scored a huge coup, convincing leaders of the California Democratic Party to endorse him.

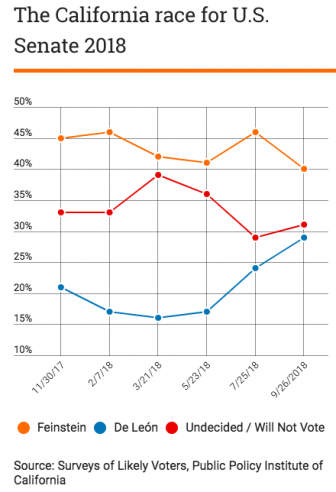

Polls still show him behind her but gaining headed into the November election when, because of California’s nonpartisan election system, voters will choose between the two Democrats. De León has strong allies. Most Democrats in the state Senate have endorsed him, including the new Senate leader, Toni Atkins, along with several in the Assembly. But 20 Democratic legislators and two of the Capitol’s most powerful figures—Gov. Brown and Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon—back Feinstein.

Some of the disconnect is about style; De León, for example, put his name on the Senate’s most important bills at the end of his tenure, while Rendon opted not to carry any legislation, shunning the associated glory. De León—sometimes taking swigs of kale or beet juice at his desk on the Senate floor—pushed an aggressive anti-Trump agenda through the upper house, including some headline-grabbing measures Rendon criticized as merely symbolic.

Rendon declined to be interviewed for this article. De León said their strained relationship is one of his biggest mistakes: “I kind of wish we had done things a little bit differently.”

Gonzalez Fletcher, the supporter who jumped in to defend his energy bill, says De León “bears the weight of being a very active, very progressive, very out-there leader, and that causes some people discomfort.”

Splitting the party is, in some ways, familiar territory for De León. He’s been a disrupter from day one.

********************************************************************************

De León often tells the story of growing up with a single mother in the San Diego barrio—it’s the subject of a new campaign ad. What he shares more reluctantly is that his mother and father were each married to other people when his mother became pregnant with him. His birth split the families that came before him, he said, and he lived alone with his mother for years before learning he had older sisters from her prior marriage.

“I struggle with that,” De León said. “You kind of feel like you just don’t have a foundation.”

His father was barely part of his life. De León and his mother, an immigrant from Guatemala, strained to get by on what she earned cleaning houses. They rented one room in someone else’s house and, throughout his early years, shared the same bed. When De León was a teenager, they rented two rooms in a basement, each one padlocked to keep out tenants living in the other rooms.

His father was barely part of his life. De León and his mother, an immigrant from Guatemala, strained to get by on what she earned cleaning houses. They rented one room in someone else’s house and, throughout his early years, shared the same bed. When De León was a teenager, they rented two rooms in a basement, each one padlocked to keep out tenants living in the other rooms.

He carried a first name he felt was too white and a last name that belonged to a near-stranger. As a kindergartner, De León remembers a teacher telling him that Kevin was an unusual name for a Latino. He recalls looking around the room at his classmates and thinking: “That’s Esteban, that’s Guillermo, that’s Manuel, that’s Miguel. And I’m Kevin.”

“I would ask my mother, ‘Why did you give me Kevin? Were you trying to make me more white? Did you feel like I’d have a better life that way, without having an overtly Spanish-sounding name?’”

No, she told him. She had heard the name while cleaning houses in the upscale parts of town. “Me gustó mucho el nombre,” he remembers her saying.

His mother died of cancer when De León was in his 20s. Some time before that he began using the Spanish word for “of” between his names: Kevin De León.

“That had to do with the feeling of wanting to belong to somebody,” he said. It also bestowed the acronym that would become his nickname—KDL.

After dropping out of UC Santa Barbara, De León began a job preparing immigrants for citizenship. He had fallen in love with a fellow student, Magdalena Carrasco, and in 1994 they marched with their baby girl in a huge protest against Proposition 187, the ballot measure—later overturned by the courts—to slash services for undocumented immigrants. (Carrasco, who is now on the San Jose City Council, remains a close friend, though they split up many years ago and he has never married.)

The campaign felt like an attack on his family, and fired his ambition. He worked for the teachers union, graduated from Pitzer College at age 36, and ran for office for the first time in 2006, defeating Christine Chavez—the granddaughter of labor icon Cesar Chavez—for a seat in the state Assembly.

********************************************************************************

Activism on behalf of immigrants has been a hallmark of his Capitol career as well. He authored the “sanctuary state” bill that was signed into law last year. Intended to stymie deportations of undocumented immigrants who commit low-level infractions, it forbids local law enforcement from coordinating with immigration authorities except in cases of serious crime. The law is being challenged in court, with mixed results.

Unsurprisingly, De León has won endorsements from major immigrant-rights groups and Spanish-language newspapers.

But Dolores Huerta—icon of the farmworker movement—is running a super-PAC to help Feinstein. She recalled De León approaching her at a labor council meeting earlier this year: “He came at me scolding me, saying ‘Why aren’t you supporting me?’ And I said, ‘Kevin, let me count the ways.’” Huerta called De León a “bully” and an “opportunist” for, in her view, dividing Democrats and disrespecting Feinstein.

But some Democrats, even some Feinstein supporters, praise De León for infusing the race with urgency, forcing the incumbent to prove herself to voters.

“No one is entitled to be automatically re-elected,” said state Sen. Scott Wiener, a San Francisco Democrat. “Kevin had every right to run. I think he brings an important perspective to the race, and Kevin has made Senator Feinstein a better candidate.”

Wiener endorsed Feinstein but said he thinks highly of De León, calling him a “substantive policy person” and “a gentleman.”

But clearly De León’s challenge of Feinstein is testing his dogged political chops. His most recent attempt to discredit Feinstein, for example, may have backfired.

After a Palo Alto woman sent Feinstein a letter saying she was assaulted by U.S. Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh, De León blasted Feinstein for holding the letter in confidence for several weeks.

He continued to criticize her even after the woman, Christine Blasey Ford, said she was pleased with how Feinstein handled the situation. Feminist Democrats skewered him for politicizing it. Lobbyist Alicia Lewis originally supported him because she wants a Latino to become California’s next senator, but says he lost her vote because his response to Ford’s dilemma was “so self-serving that it’s painful.’’

*********************************************************************************

Two days after Brown signed De León’s bill to remove fossil fuels from California’s electricity system, the senator shared a stage with New York Times columnist Tom Friedman at an environmental conference in Sausalito. The conversation focused on two issues De León has managed to link: fighting climate change and helping the needy.

California collects billions of dollars through its cap-and-trade program that makes companies pay to emit greenhouse gases. Laws written by De León require that a chunk of the funds flow to disadvantaged neighborhoods, to pay for environmental enhancements like planting trees and installing rooftop solar panels. If only wealthy people can drive electric cars and live in energy-efficient homes, De León told Friedman, global warming will be a “boutique issue.”

“We have to dig in deep and democratize our climate change benefits,” he said.

“He’s got what I think is almost a unique ability to marry climate change concerns, which are normally the province of white coastal elites, to working class people,” said R. L. Miller, chair of the California Democratic Party’s environmental caucus.

But where Miller endorses him as an “inspiring, transformational candidate,” other Democratic activists say De León’s environmental record is inconsistent. They are angered by his 2013 vote against a bill to ban plastic bags, and how he helped block a bill that would have delayed a project to suck water from the Mojave Desert.

“I’m among grassroots Democrats who have seen the senator’s actions not comport with rhetoric on a series of occasions and key policy issues,” said Hans Johnson, who lives in De León’s district and heads the East Area Progressive Democrats club, which endorsed Feinstein.

De León said he first voted against a plastic bag ban because it would have harmed workers at California factories. After negotiating terms to safeguard jobs, he voted for the revised version the next year.

His explanation for blocking the bill to stall the water project is harder to follow. The project, known as Cadiz, is supported by the Trump Administration and opposed by Feinstein, numerous other Democrats and major environmental groups. De León says he has no position on the merits of the project but blocked the bill because he didn’t like the way it was introduced, late in the legislative process.

Critics see a link between De León’s actions on the plastic and water measures: The companies fighting the legislation were both represented by a lobbying firm headed by De León’s best friend, Fabian Núñez. He was Assembly speaker when De León was first elected, but their friendship goes back much further, to boyhood in San Diego.

Also: both companies donated thousands to De León’s campaign. After environmentalists opposed to the Cadiz project drew attention to a contribution from the company, De León returned it.

“I didn’t want to give the perception that I was being influenced by a $5,000 dollar check,” he said. That was money in an account for state office; public filings show he has not returned donations to his federal campaign from Cadiz’s CEO and founder.

De León and Núñez both scoffed at the suggestion that their friendship influenced De León’s decisions. They said there have been many more instances when De León voted against Núñez’s clients.

Núñez and some of his partners at Mercury Public Affairs have donated to De Leon’s campaign, as have other Sacramento lobbyists and politicians. A smattering of well-known Californians have also written him checks—architect Frank Gehry, Laurene Powell Jobs (widow of Apple founder Steve Jobs) and Sam Altman (president of Y Combinator)—but the big money backing De León is mostly from labor unions.

Still, it doesn’t come close to the $8 million Feinstein has loaned her own campaign.

*********************************************************************************

After the clean-electricity bill was defeated on the Assembly floor, one of De León’s aides handed him a list of the votes. He pulled out a blue pen and began circling names of lawmakers he believed he could convince to change their minds.

“Now,” he said, “We’ve got to roll up our sleeves.”

He and his staff lit up a network of influential environmentalists to lobby for the bill, including Al Gore, Arnold Schwarzenegger and Tom Steyer, the billionaire who left a career as a hedge fund manager to bankroll progressive causes.

Steyer and De León forged a symbiotic friendship several years ago based on their shared concern about global warming. With Steyer’s money and De León’s political power, they have launched a complete transformation of California’s energy system. The pair collaborated in 2015 on legislation requiring half the state’s electricity to come from renewable sources, and on this year’s push to bump it up to 100 percent by 2045.

Steyer has financially supported De León’s U.S. Senate bid, albeit not at the level likely to be a game-changer. But he has spent millions to mobilize younger voters and communities of color for this election, an effort he says will help De León.

“He has been an incredibly powerful, consistent voice for a forward-looking and value-driven California,” Steyer said. “He is, I think, reflective of the best of the Democratic Party.”

By the end of the night, the clean energy bill had passed and De León was slapping backs and shaking hands on the Assembly floor.

At week’s end, after he’d cast his final votes as a state lawmaker, De León celebrated, surrounded by violins and trumpets in a Capitol hallway and singing along triumphantly to a mariachi serenade.

You didn’t have to like him, as his allies might have said, to admire his hunger, his refusal to be discounted, his willingness to disrupt all sorts of notions about California and its future, if that’s what it takes to make a change.

CALmatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics. For more stories, videos, polls and campaign finance information Election 2018, check out the CALmatters California Voter Guide.

Look above. Carrasco fined for not coming clean about deleon donors. Put deleon in the senate and he will ask for an atm machine on the floor.

As the lesser of two evils, I vote for DiFi instead of Kevin Leon.

I agree they are two evils, but I’m gonna go with Kevin. DiFi is so corrupt i just don’t see how Kevin could be anywhere near as bad has she is.

Oh, look at the story above, his sort of ex wife is the most fined council member in history. .

But he is small potato’s compared to her China connection.

Oh, yeah ask Carlos Slim. Deleon attacked him for another billionaire